In the history of art, few works have exerted such a dark and universal magnetism as Isle of the Dead by the Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin, a true cultural phenomenon that transcended museums to embed itself in the imagination of an entire era. Its unsettling visual silence captivated psychoanalysts, dictators, and revolutionaries alike, becoming an icon of the torments and obsessions of the 20th century.

Between 1880 and 1886, Böcklin (1827–1901) painted not one, but five versions of the same enigmatic scene, which are now exhibited in museums in Basel, New York, Berlin, and Leipzig. A sixth version, begun by the artist and completed by his son Carlo in 1901, is housed in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

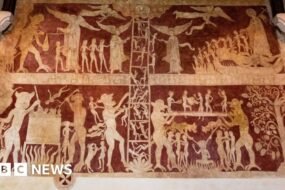

All the versions depict the same thing, a rocky and desolate islet seen across a stretch of dark, calm water where a small rowboat approaches the shore. A rower steers the vessel from the stern while at the bow, standing and looking toward the island, there is a figure dressed entirely in white. In front of this figure, a white, decorated object commonly interpreted as a coffin. The islet is dominated by a dense grove of tall, dark cypresses, trees long associated with cemeteries and mourning. In the rocky masses, one can glimpse portals and sepulchral windows.

Böcklin himself always refused to give any public explanation about the meaning of his work. He only described it as a dream image: it must produce such stillness that one would be startled by a knock at the door. The title, which was not the artist’s idea, was given by his dealer, Fritz Gurlitt, in 1883.

Without guidance from the author, many viewers turned to mythology. They interpreted the rower as Charon, the ferryman who in Greek mythology transported souls to the underworld. The water would then be the River Styx or the Acheron, and the passenger in white, a newly deceased soul in transit to the afterlife.

Origins of a Lugubrious Dream

The immediate inspiration for Isle of the Dead has deeply personal roots. The painting evokes, in part, the English Cemetery of Florence, Italy, where Böcklin painted the first three versions. This cemetery was near his studio and was also the place where his young daughter Maria was buried. A family tragedy that would repeat itself: of his fourteen children, Böcklin lost eight.

As for the model for the rocky islet, several places have been suggested. The most likely is Pontikonisi, a small, lush island near Corfu, adorned with a small chapel among a grove of cypresses. Another candidate is the mysterious rocky island of Strombolicchio, near the volcano Stromboli.

The story of how the painting multiplied is as fascinating as the image itself. Böcklin completed the first version in May 1880 for his patron Alexander Günther, but ultimately decided to keep it for himself.

While working on it, his studio in Florence was visited by Marie Berna, a young widow. She was so impressed by the unfinished “dream painting” that Böcklin created a smaller version on wood for her. At Berna’s request, who wanted an allusion to her husband’s death, the artist added the white figure and the coffin. Later, he added these same elements to the earlier version. He called these works Die Gräberinsel (“The Isle of Graves”).

The third version, painted in 1883 for his dealer Gurlitt, is perhaps the one most loaded with history. In 1933, this painting was put up for sale. A particularly notable admirer acquired it: Adolf Hitler. The Führer first hung it at the Berghof, his residence in Obersalzberg, and later, in 1940, moved it to the New Reich Chancellery in Berlin. Today, this version can be seen at the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

Economic needs led Böcklin to a fourth version in 1884. It was acquired by Baron Heinrich Thyssen, but its fate was tragic: it was destroyed after a bombing during World War II and survives only in a black-and-white photograph. A fifth version was commissioned in 1886 by the Museum of Fine Arts in Leipzig, where it remains today.

Interestingly, in 1888 Böcklin created another painting entitled Die Lebensinsel (“The Island of Life”), perhaps as an antithesis to Isle of the Dead, which also depicts a small island, but this time with all the signs of joy and life.

The Most Illustrious Admirers

The popularity of the painting soared thanks to mass reproductions. The writer Vladimir Nabokov captured this phenomenon in his 1936 novel Despair, when he wrote that reproductions of Isle of the Dead could be found in every Berlin household.

But its influence went beyond bourgeois decoration. Three of the most influential and terrible minds of the 20th century fell under its spell.

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, kept a reproduction in his office. For him, who scrutinized dreams and the unconscious, this “dream image” must have been a powerful symbol of the deepest desires and fears of the human psyche.

Vladimir Lenin, the architect of the Russian Revolution, had a reproduction hanging above his bed. It is a contradictory image: the leader who promised a materialist and scientific future, contemplating each night an allegorical journey to the beyond.

And, as already mentioned, Adolf Hitler was not content with a copy; he wanted to own one of the original versions. The painting, with its somber aesthetic and cult of death, resonated with the National Socialist mythology and its tragic and grandiose vision of destiny.

A Legacy That Crosses Artistic Borders

The impact of Isle of the Dead was not limited to painting. Its echo has resonated in music, film, literature, and video games for more than a century.

The composer Sergei Rachmaninoff dedicated a symphonic poem to it, The Isle of the Dead (1909). Curiously, the musician declared that if he had seen the original color version, he probably would not have composed the work; it was a black-and-white copy that fueled his inspiration.

In film, the horror producer Val Lewton used the painting as inspiration and backdrop for the opening credits of his 1945 movie Isle of the Dead, directed by Mark Robson. Earlier, in 1933, the design of Skull Island in King Kong showed a clear influence from Böcklin’s painting. More recently, in Alien: Covenant (2017), Ridley Scott recreated the atmosphere of the painting in the garden of the android David.

In literature, science fiction authors such as Roger Zelazny drew inspiration from it for his novel Isle of the Dead (1969). And some video games have incorporated direct references to the iconic composition.

Isle of the Dead endures because it is more than a landscape. It is an archetype. Böcklin did not paint a specific mythological scene, nor a defined religious allegory. He created an ambiguous, dreamlike space that each viewer can fill with their own fears, questions, and melancholies.

In its pictorial silence, it speaks of the final journey, of mourning, of the mystery that follows life. That is why it resonated with Freud, who wanted to map the mind; with Lenin, who wanted to remake the world; and with Hitler, who wanted to dominate it.

All three, in their quest for absolute answers, were drawn to the painting that, wisely, offers none. Its power lies precisely in that: in being a mute mirror of our eternal fascination with death and the unknown.

This article was first published on our Spanish Edition on October 1, 2025: La Isla de los Muertos, el cuadro que obsesionaba a Freud, Hitler y Lenin

Discover more from LBV Magazine English Edition

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.