It’s a face that could haunt you forever: that of the long-haired scientist peering from the shadows in Joseph Wright’s 1768 masterpiece, “An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump.” He looks out of the painting not so much at us, as beyond us — at a universe of limitless scientific possibilities, confident of his role in the betterment of humanity, despite having just killed a bird in a probably pointless scientific demonstration.

His face is seen on the posters for the National Gallery’s Wright of Derby: From the Shadows. And it’s blown-up to wall-filling size at the entrance to this revelatory exhibition on a technically prodigious artist who is all too often under-served in accounts of British art, largely, I’ve always suspected, because of that parochial appendage to his surname, ‘of Derby’.

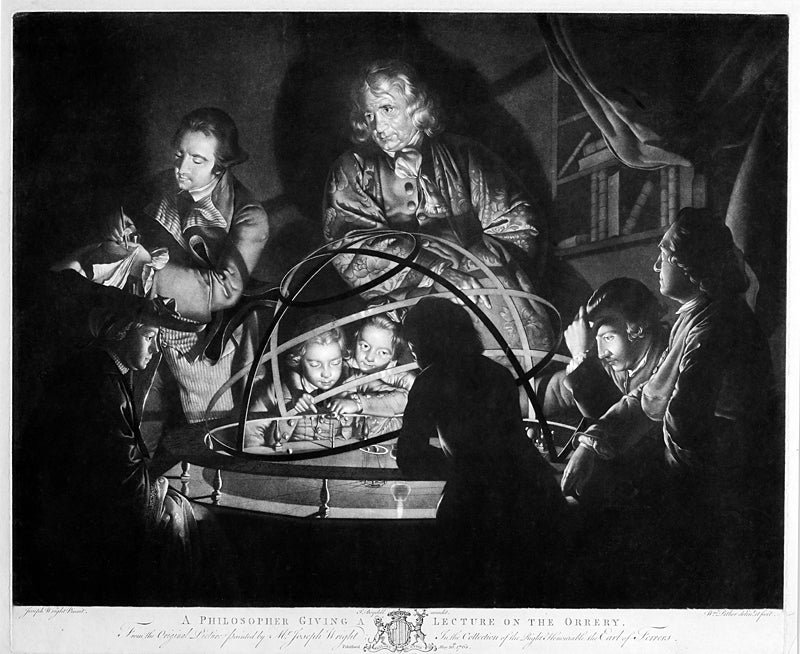

“The Air Pump” is reunited with Wright’s other great science-themed painting “The Orrery”, which shows a mechanical demonstration of the movement of the planets, for the first time in 35 years. They’re the centrepieces of a show that wants to rescue Wright from his image as a jobbing provincial painter who created the seminal images of the British scientific Enlightenment almost by accident. We’re to see Wright now not only as a singular painter of light, but an artist who ‘proposes moral questions about the act of looking’.

Born in Derby in 1734, Wright was not only prodigiously gifted as an artist, but a highly astute businessman. Having trained in London, he returned to the West Midlands to capitalise on the build-up of new money in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. He developed a style based on the chiaroscuro of 17th century painters such as Caravaggio, with heightened realism and powerful contrasts of light and shadow, precisely because it would appeal to rich young men who had taken the Grand Tour. While he produced paintings in this vein for only eight years (from 1765 to 1773), they’ve been considered his most distinctive works from his day to ours. Several of the best known are brought together here.

If Wright has been described as ‘the first professional painter to express the spirit of the Industrial Revolution’, the feel in “A Blacksmith’s Shop” (1771) is primal and visionary rather than technocratic. The spot-lit central figure pounding a piece of white-hot metal in his nocturnal smithy is a character straight out of myth. The modest scale of “The Alchymist in Search of the Philosopher’s Stone” (1771) belies its epic mood, as the titular figure kneels in prayer for divine assistance as he inadvertently discovers phosphorus, rather than the means to turn base metals into gold. The atmosphere, again, is mystical, even gothic, a reminder that the gap then between “hard science” and what we’d dismiss today as mumbo-jumbo was far narrower than we’d imagine, even for great scientific figures like Isaac Newton.

Whatever the extent of Wright’s scientific knowledge, he had a formidable understanding of artistic genres and the manipulation of metaphor. In “An Academy by Lamplight”, a group of students cavort in the shadows around a brightly lit classical statue of a nymph with a shell. Only one bothers to draw her. Lived experience, we might construe, is more important than rote learning from the past.

But it’s those large-scale “scientific” tableaux that dominate the proceedings. Far from depicting cutting-edge innovation, they show stock experiments performed by itinerant ‘lecturers’ as entertainment in wealthy homes.

The family members cluster excitedly round the demonstration table in each of the paintings, as the “godlike” figure of the lecturer looms above them. Two little boys gaze in delight at the moving model of the planets in “The Orrery”, as a third child’s silhouette blocks our view of the lamp representing the sun, throwing an unearthly glow over the faces of the onlookers. The boys’ excitement contrasts with the horror of their female counterparts in “The Air Pump”, sobbing at the bird’s death as the pump draws air from a glass vessel.

This modest element of drama inevitably gives this painting the greater edge. Every character’s expression feels totally credible, from the man, presumably the girls’ father, reassuring them they are simply observing the workings of nature, to the young couple, too preoccupied with flirting to care. But it’s the haunting expression of the “lecturer” that draws us. While he is essentially a not-so-cheap entertainer, providing ‘improving’ amusement to the gentry, he’s portrayed as an ambiguously visionary figure, in touch with realities beyond the comprehension of the rest of us. His sober, authoritative counterpart in “The Orrery” is designed, we are told, to evoke the figure of Newton, the scientist who came closest to rivalling God in terms of defining physical causation in the universe.

If Wright is preoccupied with the morality of the act of looking, as the exhibition argues, it’s our own looking that feels most in question. Beneath these scenes of educational family entertainment at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution there’s a palpable sense of unease, or certainly a questioning, of the idea of the scientist playing God, and manipulating the rest of us in the process. These images couldn’t be more painfully relevant to the age of AI, when technology appears in the process of rendering “humanity”, in all senses, redundant, and by means which the vast majority of us completely fail to comprehend.

‘Wright of Derby: From the Shadows’ is at the National Gallery from 7 November 2025 until 10 May 2026