Highly activated NKG2A/PD-1 double positive T cells are present in the tumour microenvironment of HNSCC patients

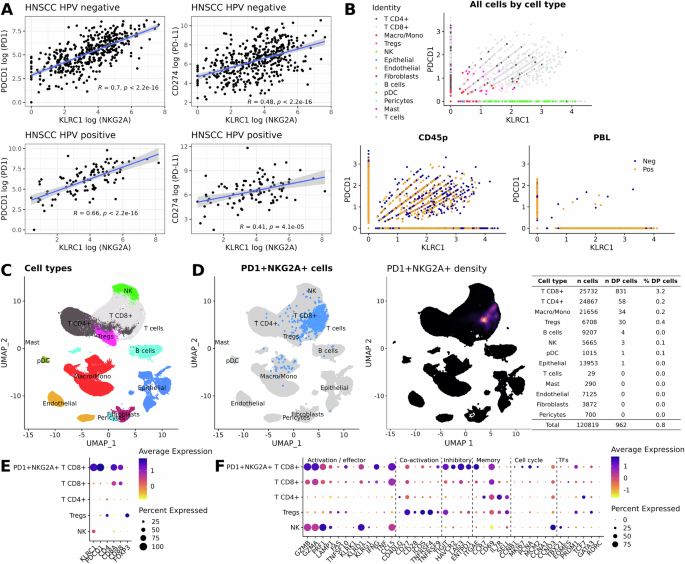

The combination of anti-NKG2A and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 axis ICB has recently gained momentum in clinical settings, particularly in lung cancer. Reinvigoration of NKG2A/PD-1 double-positive cytotoxic lymphocyte cells in the tumour microenvironment (TME) could provide a mechanistic basis for the combination, including in HNSCC. Thus, we interrogated published databases in patients with HNSCC. First, analysis of the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) revealed a significant positive correlation between expression of KLRC1 (NKG2A) and both PDCD1 (PD-1) and CD274 (PD-L1) in HPV– and HPV+ HNSCC tumours (Fig. 1A). To identify the type of immune cells expressing both KLRC1 and PDCD1, we analysed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) databases available in two previously published articles19,20. Interestingly, KLRC1/PDCD1 double-positive immune cells were detected in both studies and those cells were predominantly present in tumours rather than blood (Fig. 1B and S1A). Further detailed analyses also showed that the majority of KLRC1+/PDCD1+ cells were in the CD8+ T cell compartment (Fig. 1C, D and Fig. S1B, C). Tumour HPV status did not affect the frequencies of KLRC1/PDCD1 double-positive CD8 and CD4 T cells (Fig. S2). Additionally, we observed that KLRC1/PDCD1 double-positive CD8 T cells were highly activated, as shown by high expression of cytotoxic/effector/memory/proliferating lymphocyte gene signatures including GZMA, GZMB, PRF-1, IFNG, CCL5, TIGIT, LAG3, ITGAE, CD69 and PCNA (Fig. 1E, F and Fig. S1D, E).

A TCGA database analyses of the correlation between expression of KLRC1 and both PDCD1 and CD274 in both HPV– and HPV+ HNSCC patients. The blue line and the shaded area indicate the linear regression fit with the 95% confidence interval; two-tailed test p-values are provided for Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. B Scatter plots showing expression of KLRC1 and PDCD1 in various cell populations (higher panel) and tumours versus blood (lower panels). C UMAP plot showing distribution of identified cell clusters distribution. D Left panel; UMAP plot depicting NKG2A/PD-1 double positive cells in the different identified cell clusters, right panel; UMAP plot depicting intensity expression of NKG2A/PD-1 double positive cells with absolute numbers for each identified cell populations (right table). Dot plots showing average and percentage expression of the KLRC1, PDCD1 and pan-cell markers (E) and activation/effector, co-activation, inhibitory, memory, cell cycle and transcription factors (TFs) markers (F) in NKG2A+/PD-1+ CD8+ T cells versus CD8+T, CD4+T, Tregs and NK cells. Datasets from Kurten et al.19.

Taken together, these analyses of previously published scRNAseq datasets show the presence of highly activated NKG2A/PD-1 double-positive CD8 T cells in the TME of patients with HNSCC and point towards opportunities for their clinical exploitation.

Dual anti-NKG2A and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade enhances ATRi/RT-mediated antitumour response in head and neck cancer preclinical models

Because of the high activation status of NKG2A/PD-1 double-positive T cells and their potential as therapeutic targets, we tested whether combination of ATRi and RT increased the number of these cells in the TME using both HPV– (MOC1) and HPV+ (mEER) preclinical models21,22,23.

We confirmed that combined ATRi/RT delayed tumour growth and increased survival in both models when compared to single-agent treatment (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3A). Critically, ATRi/RT led to an increase of the proportions of both NKG2A/PD-1 double-positive CD8 and CD4 conventional (CD4conv) T cells in both MOC1 and mEER ectopic (subcutaneous) tumours (Fig. 2B and Fig. S3B, C). Importantly, the addition of ATRi to RT was critical for the infiltration of such cells into tumours (Fig. S4A). Those cells were more activated than their NKG2A/PD-1 double-negative counterparts, as shown by higher expression levels of activation/memory/proliferation markers, such as CD44, CD69, GZMB, ICOS, PRF-1, Ki67, KLRG1, NKG2D and TIM-3 (Fig. 2C). Despite a less pronounced difference in the expression of the various markers, NKG2A/PD-1 double-positive populations displayed generally a higher activation status than the PD-1 single-positive populations, (Fig. 2C). Of note, increased proportions of NKG2A/PD-1 double-positive CD8 and CD4conv T cells were accompanied by a greater number of cancer cells expressing both Qa-1b and PD-L1, the ligands for NKG2A and PD-1, respectively (Fig. 2D and Fig. S3D). These results strengthen the hypothesis that ATRi/RT can create a TME in which the NKG2A/Qa-1b and PD-1/PDL-1 axes might favourably be targeted concomitantly.

Experiments in this figure were performed in the MOC1 model. A Tumour growth and survival curves across the different conditions (Control n = 10, ATRi n = 11, RT n = 11, ATRi/RT n = 11; combined from two independent experiments). B Bar chart; % of NKG2A and/or PD-1 positive populations in CD8 and CD4conv T cells, scatter plot with bar; NKG2A/PD-1 positive populations in CD8 and CD4conv T cells (Control n = 8, ATRi/RT n = 12; combined from two independent experiments). C Heatmap showing marker intensity of expression in NKG2A+/PD-1+ versus NKG2A−/PD-1− CD8 and CD4conv T cells. D % surface expression of Qa-1b/PD-L1 double positive cancer cells in the different conditions (Control n = 8, ATRi/RT n = 8; from one experiment). Tumour growth and survival curves across the different conditions in ectopic (E; control n = 17, αNKG2A/αPD-L1 n = 17, ATRi/RT n = 16, ATRi/RT/αPD-L1 n = 12, ATRi/RT/αNKG2A/αPD-L1 n = 17; combined from three independent experiments) and orthotopic (F; Control n = 8, αNKG2A/αPD-L1 n = 5, ATRi/RT n = 10, ATRi/RT/αPD-L1 n = 6, ATRi/RT/αNKG2A/αPD-L1 n = 12; combined from two independent experiments). G Tumour growth in control versus rechallenged mice (Rechallenge n = 5, Control n = 6; from one experiment). Results are shown as means ± SEM and n represents number of mouse/groups. Parametric statistics were only applied to normally distributed data. Numbers on graphs represent P values and were determined by Two-tailed Unpaired t test (A, CD4conv T cells and D), Two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (A, CD8 T cells) and Log-Rank Mantel–Cox test (C, E, F).

Next, mice bearing ectopic MOC1, MOC2 (both HPV–), mEER and TC1 (both HPV+) tumours received systemic anti-NKG2A and/or anti-PD-L1-blocking antibodies after ATRi/RT. Interestingly, the combination of both anti-NKG2A and PD-L1 antibodies significantly improved ATRi/RT treatment in terms of tumour growth and survival in all models (Fig. 2E, Fig. S3E and Fig. S5A, B). The addition of anti-NKG2A was necessary, as anti-PD-L1 antibody treatment alone exerted relatively modest benefits. The addition of ATRi was essential for efficacy of the full combination therapy (Fig. S4B). Importantly, the actual therapeutic benefit of having the full combination of ATRi/RT/anti-NKG2A/anti-PD-L1 was further confirmed orthotopically in both MOC1 and mEER models. When compared with the other treatment groups, mice treated with the full combination had better tumour control (Fig. 2F and Fig. S3F). Previously cured animals did not develop tumours on rechallenge in both models (Fig. 2G and Fig. S3G). Importantly, the full combination therapy did not trigger significant toxicity, as assessed by weight loss, throughout treatment duration in all models studied (Fig. S6).

Finally, the crucial importance of intact tumour-draining lymph nodes (TDLN) in generating and sustaining an effective anti-tumour immune response and, thereafter, clinically meaningful responses to ICB, is increasingly recognised. We, therefore, sought to validate that radiotherapy delivery in our lip orthotopic pre-clinical studies was tumour site-specific by using γ-H2AX staining as an acute radiobiological readout (Fig. S7). Unirradiated tissues showed marginal γ-H2AX staining when compared to the tumour irradiation group, where only tumours, and not TDLNs or uninvolved LNs, showed high levels of γ-H2AX staining. Irradiation of both tumours and TDLNs in separate radiation fields yielded high levels of γ-H2AX staining in both the tumour and TDLN with no signal present in the distant, unirradiated sub-iliac LN (Fig. S7).

Taken together, these data show that ATRi/RT increased the frequencies of both NKG2A+/PD-1+ CD8 and CD4conv T cells, alongside Qa-1b+/PD-L1+ cancer cells in the TME. Subsequent adjuvant therapy with NKG2A and PD-L1 blocking antibodies after ATRi/RT stimulated favourable effector and memory antitumour immunity in both HPV- and HPV+ head and neck cancer preclinical models.

Combination of ATRi/RT and anti-NKG2A/PD-L1 dual immune checkpoint blockade induces gene signatures characteristic of T cell activity

To study the nature of the antitumour immune response following ATRi/RT, we performed RNA sequencing (RNAseq) in MOC1, mEER and MOC2 tumours on day 11 post-radiation (8 days after the beginning of immunotherapy). Differential gene expression (DEG) analysis showed significant changes induced by ATRi/RT, which were further increased by adding immunotherapy (Fig. 3A, Fig. S8A and Fig. S9A). Volcano plots also revealed higher expression of genes typical of an immune response, such as PRF-1, CD274 and CD8a, when mice were treated with the full combination therapy (Fig. 3B, Fig. S8B and Fig. S9B).

Experiments presented in this figure were performed in the MOC1 model. RNAseq experiments were performed with n = 4 for each group (A) Number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across the different conditions calculated by DESeq2 using Wald test. B Volcano plots showing expression of the different genes in the various conditions (genes characteristic of an immune response are named). C Immune cell population estimates. Immune cell scoring was performed on normalised RNAseq counts using the mMCP-counter package. Heatmaps corresponding to interferon and cytokine signalling, chemoattractant, MHCI and MHCII (D); immune cell populations (E); and immune cell activation status (F). Data shown are z-scores of log2 transformed normalised counts for the treatment conditions shown. This plotted alongside log10 adjusted p-value for each gene calculated from DEG analysis using Wald test. Non-significant adjusted p-values > 0.05 are indicated as grey. G Absolute number/gram of tumour of the indicated lymphocytes in the various conditions (Control n = 8, ImmuT n = 7, ATRi/RT n = 12, ATRi/RT/ImmuT n = 12; combined from two independent experiments). H % Ki67-positive cells in the indicated lymphocytes in the different conditions (Control n = 8, ImmuT n = 7, ATRi/RT n = 12, ATRi/RT/ImmuT n = 12; combined from two independent experiments). I % indicated lymphocytes in the total T cell population across all treatment conditions (Control n = 8, ImmuT n = 7, ATRi/RT n = 12, ATRi/RT/ImmuT n = 12; combined from two independent experiments). J Tumour growth curves across all conditions (Control n = 5, ATRi/RT/ImmuT n = 6, ATRi/RT/ImmuT/aNK1.1 n = 5, ATRi/RT/ImmuT/aCD8 n = 6; from one experiment). K Tumour growth and survival curves across the different conditions (Control n = 5, ATRi/RT/ImmuT n = 5, ATRi/RT/ImmuT/aCD8 n = 5, ATRi/RT/ImmuT/aCD4/CD8 n = 6; from one experiment). Results are shown as means ± SEM and n represents number of mouse/groups. Parametric statistics were only applied to normally distributed data. Numbers on graphs represent P values and were determined by Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test (G; CD8 T cells, CD4reg T cells and NK cells; H; CD8 T cells, CD4reg T cells and NK cells), ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (G; CD4conv T cells and H; CD4conv T cells), Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test from area under curve (J) and Log-Rank Mantel–Cox test (K). Significant outliers were removed using Grubb’s test.

Immune cell population estimates from transcriptomic data, using mMCP-counter, highlighted the prominence of T cells in all models in response to treatment (Fig. 3C, Fig. S8C and Fig. S9C). However, there were some differences between models in the case of monocytes, granulocytes and fibroblasts. Analysis of single gene expression showed that, in both MOC1 and MOC2 models, ATRi/RT/anti-NKG2A/anti-PD-L1 (ATRi/RT/ImmuT) combination, when compared with the other groups, regularly induced more interferon signalling (CD274, RSAD2, ISG15, IFIH1, DDX60 and ZPD1), chemoattraction (CCL5, CCL9 and CXCL10), MHCI- (H2-Aa, H2-D1, H2-M3 and H2-T23) and MHCII-related (H2-AA, H2-AB1, H2-EB1, CD74 and H2-DMB1) gene expression (Fig. 3D and Fig. S9D). Generally, differences were less pronounced in the mEER model, with the exception of MHCII-related genes (Fig. S8D). For immune cell population gene signatures, in response to ATRi/RT/ImmuT, the lowest numerical p-values were observed for various NK cell receptors, such as KLRD1, KLRC1 and KLRK1 in MOC1/MOC2 tumours but only KLRD1 and KLRK1 in mEER tumours (Fig. 3E, Fig. S8E and Fig. S9E). It is remarkable that, in all models, we observed greater increases of genes characteristic of T cell activity, including CD3D, CD3E, FOXP3 and CD8A, in response to ATRi/RT/ImmuT (Fig. 3E, Fig. S8E and Fig. S9E). Finally, we also detected in the same treatment group high expression of genes for immune cell activation markers, including GZMB, PRF1, PDCD1, HAVCR2, ICOS, TNFRSF4, CD40, CD27 and CD28, in all tumours (Fig. 3F, Fig. S8F and Fig. S9F).

Together, RNAseq analysis suggests that ATRi/RT and anti-NKG2A/PD-L1 dual immune checkpoint blockade triggers a robust immune response in the TME, which is likely to be mediated by the activity of T cells in both HPV– and HPV+ head and neck cancer models.

The efficacy of the combination of ATRi/RT and anti-NKG2A/PD-L1 immunotherapy is dependent on the activity of both CD8 and CD4 T cells

To confirm the RNAseq results, we performed flow cytometry analyses in both MOC1 and mEER tumours. The lymphocyte data revealed that full combination therapy with ATRi/RT/ImmuT significantly induced greater infiltration of CD8, CD4conv and CD4 regulatory (reg) T cells, as well as NK cells, into the TME in both models in comparison with the other treatment groups (Fig. 3G and Fig. S8G). Of note, ATRi/RT or ImmuT on their own did significantly boost the infiltration of some lymphocyte subtypes, such as CD8 and CD4conv T cells, in some instances. Importantly, however, only the full ATRi/RT/ImmuT combination led to a significant improvement of lymphocyte activation as demonstrated by increased intracellular expression of the pan-activation/proliferation marker Ki67 (Fig. 3H and Fig. S8H). In addition, in respect of T cell compartment, ATRi/RT/ImmuT caused increased frequencies of CD8 T cells (Fig. 3I and Fig. S8I). Finally, to prove specific reactivity of T cells towards tumour antigens, we restimulated splenocytes from mEER tumour-bearing mice treated with the different therapies with a long overlapping HPV16 E7 peptide pool. Only full combination therapy significantly increased the proportions of both CD8 and CD4conv T cells with proliferative and cytotoxic capacities (Fig. S8J).

In light of those data, we defined the subtypes of lymphocytes mediating treatment efficacy using specific depleting antibodies. In mice treated with ATRi/RT/ImmuT, the acceleration of tumour growth and shortened lifespan in the absence of CD8 T cells demonstrated the crucial role of those cells in mediating therapy in the MOC1 and MOC2 models (Fig. 3J and Fig. S9G). The effect of CD8 T cells was even more marked in the mEER model (Fig. S8K). In contrast to CD8 T cells, however, depletion of NK cells did not have a significant effect on the efficacy of the full combination treatment, except in the MOC2 model (Fig. 3J, Fig. S8K and Fig. S9G). Strikingly, the depletion of both CD8 and CD4 T cells in MOC1-bearing mice completely abrogated the effect of the full combination therapy in terms of mouse survival (Fig. 3K). Delayed separation between the tumour growth curves of CD8 and CD8/CD4 T cell-depleted mice suggests a delayed role for CD4 T cells.

Taken together, these data suggest that the efficacy of ATRi/RT/ImmuT combination therapy is dependent on the infiltration of both activated CD8 and CD4 T cells in the TME.

Combination of ATRi/RT and anti-NKG2A/-PD-L1 immunotherapy promotes the infiltration of CD8 and CD4conv T cell subpopulations with a PD-1high cytotoxic/proliferative/effector memory phenotype

Next, we sought insight into the specific phenotypes of therapy-related tumour-infiltrating CD8 and CD4 T cells. Thus, we performed extensive immune profiling in the MOC1 model, using a combination of TriMap and FlowSOM algorithms to identify the various clusters of CD8 and CD4 T cell populations in control and treatment groups.

We observed a disappearance of naïve/inactivated CD8 and CD4 T cell populations (pop 4 and 0, respectively) from MOC1 tumours. These populations were diminished in the ATRi/RT cohort and completely absent in response to the full combination therapy (Fig. 4A, B). In parallel, a shift towards populations with an activated/proliferative phenotype for CD8 T cells was identified in response to ATRi/RT (pop 6 and 7), but this effect was accentuated after the addition of immunotherapy (pop 2 and 3) (Fig. 4A). The same pattern was detected for CD4conv T cells, with populations displaying more pronounced activated/proliferative phenotypes (pop 3, 4, 6 and 9) in the full combination therapy when compared with ATRi/RT alone. By contrast, adding immunotherapy to ATRi/RT did not significantly modulate the various populations of CD4reg T cells when compared with ATRi/RT alone (Fig. 4B).

Experiments presented in this figure were performed in the MOC1 model. A, B Higher panels; intensity of the different subpopulation clusters of CD8 (A) and CD4 (B) T cells identified using TriMap and FlowSOM algorithms, lower panels; heatmap showing the expression of the indicated markers in the different populations identified by FlowSOM algorithm across all treatment conditions (concatenated from Control n = 7, ATRi/RT n = 8, ATRi/RT/ImmuT n = 8; from one experiment). C Dot plot and donut chart representing % of CD8 and CD4conv T cells in the different cell cycle phases across all conditions (concatenated from Control n = 5, ATRi/RT n = 6, ATRi/RT/ImmuT n = 6; from one experiment). Across all conditions the following graphs show % (D) PD-1+, (E) ICOS+, (F) naïve (N; CD62L+ CD44–), effector (EM; CD62L– CD44+ CD103–) and tissue-resident (TRM; CD62L– CD44+ CD103+) memory, (G) Ki67/PRF+ EM, (H) NKG2D+ and (I) T-BET+ CD8 and CD4conv T cells (Control n = 15, ATRi/RT n = 17, ATRi/RT n = 17; combined from two independent experiments). Results are shown as means ± SEM and n represents number of mouse/groups. Parametric statistics were only applied to normally distributed data. Numbers on graphs represent P values and were determined by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test (E; CD8 T cells; F; CD8 TN, CD4conv TN, CD8 TEM, CD4conv TTRM; G; CD8 T cells) or ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (E; CD4conv T cells, F; CD4conv TEM, CD8 TTRM; G; CD4conv T cells; H, I).

The key findings from TriMap/FlowSOM analyses were further investigated to evaluate their significance. Since increased proliferation was an important feature of T cell subpopulations infiltrating MOC1 tumours after full combination therapy, we tracked cell cycle distribution in CD8 and CD4conv T cells. ImmuT added to ATRi/RT caused a noticeable shift of both CD8 and CD4conv T cells towards G2/M phase, which suggests the presence of actively dividing cells (Fig. 4C). At the same time, we observed that ATRi/RT/ImmuT was instrumental in increasing the frequencies of PD-1+ (Fig. 4D), ICOS+ (Fig. 4E) and effector memory (EM) (Fig. 4F) CD8 and CD4conv T cells. In line with the TriMap/FlowSOM analysis, MOC1 tumours were more infiltrated with Ki67/PRF1+ CD8 and CD4conv TEM cells in response to the full combination (Fig. 4G). We also detected elevated frequencies of NKG2D+ and T-BET+ CD8 and CD4conv T cells in the same treatment group when compared with ATRi/RT alone (Fig. 4H, I).

To evaluate the specific effect of including anti-NKG2A antibody in full combination therapy at the cellular level, we performed the same set of experiments, comparing the key subpopulations of both CD8 and CD4conv T cells previously described between ATRi/RT, ATRi/RT/anti-PD-L1 and ATRi/RT/anti-NKG2A/PD-L1 treatment groups. Interestingly, blocking NKG2A was critical in shifting the cell cycle in CD8 T cells from G0/G1 to G2/M phases, and the same effect was seen in CD4conv T cells (Fig. S10A). These data were further reinforced by the significant increase of Ki67+ cells in the treatment cohort that included anti-NKG2A (Fig. S10B). Adding anti-NKG2A also enhanced the frequencies of both PD-1+ CD8 and CD4conv T cells and ICOS+ CD4conv T cells (Fig. S10C, D). Anti-NKG2A antibody significantly promoted the effector memory phenotype, which correlated with increased proportions of Ki67/PRF1+ CD8 and CD4conv TEM cells (Fig. S10E, F). Finally, the inclusion of anti-NKG2A in combination therapy crucially elevated the frequencies of NKG2D- and T-BET-positive CD8 and CD4conv T cells (Fig. S10G, H).

Taken together, these data indicate that ATRi/RT/anti-NKG2A/PD-L1 combination therapy leads to the infiltration of PD-1high/cytotoxic/proliferative/effector memory CD8 and CD4conv T cells in the TME. In parallel and importantly, the nature of CD4reg T cell populations following ATRi/RT is not affected by the addition of anti-NKG2A/PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade.

CD40 signalling mediates antitumour immunity in response to ATRi/RT/anti-NKG2A/PD-L1 combination therapy

As described above, prominent subpopulations of both CD8 and CD4conv T cells in the TME following ATRi/RT/ImmuT were characterised by high surface expression of PD-1. We detected in similar experiments enhanced expression of CD40L on those PD-1+ T cells, i.e., the most activated cells (Fig. 5A). In parallel, the same treatment conditions led to an increase of CD40high cDC1, cDC2 and pDCs, as well as CD40+ monocytes, macrophages and neutrophils (Fig. S11A, B). These findings prompted evaluation of whether CD40/CD40L signalling was a potential costimulatory pathway responsible for the therapeutic effect seen.

Experiments presented in this figure were performed in the MOC1 model. A % of PD-1/CD40L double positive CD8 and CD4conv T cells across indicated treatment conditions (Control n = 10, ATRi/RT n = 12, ATRi/RT/ImmuT n = 15; combined from three independent experiments). B Tumour growth and survival curves across the different conditions (n = 5 for each group; from one experiment). C Tumour weight collected from mice in the indicated conditions (n = 10 for each group; from one experiment). D Absolute number/gram of tumour tissue of CD8 and CD4conv T cells in the various conditions (n = 10 for each group; from one experiment). % PD-1+, Ki67+ and PRF/NKG2D+ CD8 (E) and CD4conv (F) T cells in treatment conditions (n = 10 for each group; from one experiment). G TCGA database analyses of the correlation between expression of KLRC1 and PDCD1 with CD40 and CD40LG in both HPV– and HPV+ HNSCC patients. The blue line and the shaded area indicate the linear regression fit with the 95% confidence interval; two-tailed test p-values are provided for Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. Results are shown as means ± SEM and n represents number of mouse/groups. Parametric statistics were only applied to normally distributed data. Numbers on graphs represent P values and for in vivo experiments were determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (A); Log-Rank Mantel–Cox test (B) and Two-tailed Unpaired t test (C–F). Significant outliers were removed using Grubb’s test.

Indeed, we found that stimulation of CD40 following ATRi/RT significantly reduced tumour burden (Fig. S10C), whereas interfering with CD40/CD40L signalling abrogated the additive therapeutic effect of immune checkpoint blockade (Fig. 5B, C). Furthermore, blocking this costimulatory pathway decreased infiltration of both CD8 and CD4conv T cells (Fig. 5D) and remaining tumour-infiltrating CD8 and CD4conv T cells lost PD-1 expression, effector memory status, proliferative and cytotoxic capacities (Fig. 5E, F). Finally, to highlight the translational potential of this findings, analysis of the TCGA database revealed that both CD40 and CD40LG expression significantly correlated with KLRC1 and PDCD1 expression in HNSCC patients, regardless of their HPV status (Fig. 5G).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that CD40/CD40L signalling plays a key role in mediating the full efficacy of ATRi/RT/ImmuT by promoting the infiltration and activation of highly activated, proliferating CD8 and CD4conv T cells.

Combination of ATRi/RT and anti-NKG2A/-PD-L1 immunotherapy significantly affects the dynamics of TCR activity

To study the temporal progression and dynamics of T cell activity in response to combination therapies, we used the recently developed ‘’Timer and Cell Kinetics and Activity” (Tocky) system24,25. Tocky is a reporter system based on a fluorescent ‘Timer’ protein, which spontaneously changes its emission from blue to red within 4 h (Fig. 6A). The red-form protein is stable, so its maturation allows flow cytometric-based monitoring of rapid temporal changes in expression. By using transgenic mice in which the expression of fluorescent Timer protein is synchronised with the Nr4a3 gene (Nr4a3-Tocky), we can study the induction of TCR activation. Resting T cells do not express the Timer protein (negative signal) but, once T cells recognise cognate antigen and receive TCR signals, Timer transcription is initiated and they become blue+ red– (new signal). T cells with persistent TCR signalling sustain Timer transcription over time and accumulate both blue+ and red+ proteins (persistent signal). When T cells disengage from their antigens, Timer transcription is arrested, and the unstable blue– protein is lost, resulting in T cells becoming blue– red+ (arrested signal) (Fig. 6A).

Experiments presented in this figure were performed in the MOC1 model. A Higher panel; schematic explaining production and decay of the Timer protein; lower panel: gating strategy for the detection of the different Timer populations, negative, new, persistent and arrested. B Dot plots showing the % of the different Timer population in NKG2A–/PD-1–, NKG2A+/PD-1–, NKG2A–/PD-1+ and NKG2A+/PD-1+ CD8 and CD4conv T cells (concatenated n = 6; from one experiment). C % of the indicated Timer population in CD8, CD4conv and CD4reg T cells across all conditions (Control n = 10, ATRi/RT n = 12, ATRi/RT/ImmuT n = 15; combined from three independent experiments). D UMAP plot showing Tocky angle and expression intensity as well as indicated markers expression intensity (concatenated from n = 14, independent of condition from one experiment). Results are shown as means ± SEM and n represents number of mouse/groups. Parametric statistics were only applied to normally distributed data. Numbers on graphs represent P values and were determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (C). Significant outliers were removed using Grubb’s test.

NKG2A/PD-1 double-positive CD8 and CD4conv T cells were characterised by increased frequencies of persistent TCR activation when compared to other subpopulations (Fig. 6B). Additionally, CD40L+ CD8 and CD4conv T cells were more persistent than the CD40L– population (Fig. S12A). The action of combined ATRi/RT/ImmuT significantly reduced the proportions of Timer-negative CD8 and CD4conv T cells, which demonstrated enhanced TCR engagement (Fig. 6C). No variations were observed in terms of new TCR signalling in CD8 T cells across all treatment groups (Fig. 6C). In contrast, we observed significantly higher proportions of new TCR signals in CD4conv T cells with the addition of ImmuT to ATRi/RT (Fig. 6C). Whilst there was a trend towards a decrease in the same new Timer population in CD4reg T cells, we detected a significant increase in the frequencies of CD8 T cells with persistent TCR signal in response to ATRi/RT/ImmuT (Fig. 6C). Trends for increased proportions of persistent CD4conv T cells were found in both ATRi/RT and ATRi/RT/ImmuT treatment groups (Fig. 6C). Persistence of TCR activation in both CD8 and CD4conv T cells was significantly dependent on CD40/CD40L signalling (Fig. S12B, C). There was no impact in the frequencies of arrested TCR signalling in all T cells under any treatment condition. Interestingly, populations of CD8 and CD4conv T cells with high Timer intensity were enriched for PD-1 and CD44 but devoid of CD62L, which highlighted their PD-1+ effector memory status (Fig. 6D), as shown by Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) analysis of Timer Angle and Intensity with markers26.

Taken together, these data show unique dynamics of TCR activity from the various populations of T cells in the TME after treatment. Only with the full ATRi/RT/ImmuT combination did CD8 T cells display more persistent TCR activation, while CD4conv T cells exhibited more recent TCR engagement. Importantly, however, the dynamics of TCR activity in CD4reg T cells was not significantly impacted by the different therapeutic regimens, suggesting a more prominent T cell signalling function for CD4conv T cells in cooperation with CD8 T cells.

Combination of ATRi/RT and anti-NKG2A/PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade induces variations of TCR repertoires in tumours

To follow up on Tocky analyses and to explore further the amplitude of T cell antitumour response, we subsequently evaluated TCR repertoires in response to different therapy groups. RNA-based targeted sequencing of the CDR3B chain of the TCR was performed from fresh-frozen tumours from mice under three different conditions (control, ATRi/RT and ATRi/RT/ImmuT).

Only the ATRi/RT/ImmuT combination was associated with a significantly higher number of absolute unique productive clonotypes compared to the control, which suggests an increase in TCR repertoire richness (Fig. 7A). Next, Gini Simpson coefficient was used to quantify clonality across the different conditions. We found that only the full combination showed a significantly higher TCR repertoire clonality compared to the control, suggesting intra-tumoral T-cell expansion (Fig. 7B). However, no differences were found between the ATRi/RT and the addition of ImmuT. This was also confirmed when exploring the proportion of the repertoire occupied by the first quintile (Q1), which was found to be higher compared to the control in both ATRi/RT and ATRi/RT/ImmuT arms (Fig. 7C, D). The V- and J-usage did not significantly change across the different conditions, although a trend towards an increase in the even distribution of the V- and J- gene segment pairing was observed when immunotherapy was added to ATRi/RT (Fig. 7E). When clustering the expanded TCRs by CDR3B triplet amino acid similarity (Fig. 7F), we found that only the full combination displayed a significant increase in the normalised cluster count compared to the control (Fig. 7G). Furthermore, these clusters of closely similar TCR clonotypes were not only more abundant, but also bigger in size in the ImmuT-containing combination, as shown when comparing the number of dominant clusters defined as those formed by ≥3 expanded clonotypes (Fig. 7G). This observation strongly supports the notion that the addition of ImmuT to ATRi/RT leads to preferential expansion of large clusters of antigen-sharing T-cell clonotypes, which may reflect enhanced stimulation by increased antigen cross-presentation and T-cell priming, and/or the ability of this combination to promote primed T-cell activation and expansion. Furthermore, the effect of adding anti-CD40L to the triple combination was interrogated. Blocking treatment with anti-CD40L significantly affected the TCR repertoire by abolishing the effect of ATRi/RT/ImmuT in TCR richness (Fig. S13A), clonality (Fig. S13B, C) and antigen-sharing clustering (Fig. S13D, E).

One single experiment was performed with n = 3 for each group in the MOC1 model. A Absolute number of unique productive clonotypes across the different conditions. B Clonality (Gini Simpson coefficient) across different conditions. C Comparison of the proportion (in percentage) of the TCR repertoire occupied by the first quantile of clonotypes. D Clonality plots for each condition. The plots present 3 layers to visualise the TCR repertoire clonality: the first layer includes the frequency of singleton (“1”, met once), doubleton (“2”, met twice) and high-order (“3+”, met three or more times) clonotypes; the second layer (“quintile”), displays the abundance of top 20% (“Q1”), next 20% (“Q2”), … (up to “Q5”) clonotypes for clonotypes from “3+” set; and the last layer (“top”) displays the individual abundances of top 5 clonotypes. E Representative of V–J junctions by circus plot for each condition. Arcs correspond to different V and J segments, scaled to their frequency in samples and ribbons represent V–J pairings and their size is scaled to their pairing frequency. F Network diagrams of CDR3B amino acid triplet clusters for each condition. Clusters containing expanded CDR3s are shown. G Comparison of normalised cluster count and dominant cluster count for each condition. Results are shown as means ± SEM and n represents number of mouse/groups. Parametric statistics were only applied to normally distributed data. Numbers on graphs represent P values and were determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (A–C, G).

Together, this strongly suggests that the intra-tumoral adaptive immune effects of ATRi/RT and ATRi/RT/ImmuT require engagement of CD40-CD40L signalling, contributing to T cell expansion and TCR repertoire remodelling.