Say “Gödel, Escher, Bach”—which is the title of a 1979 book by Douglas Hofstadter—to Rm. Palaniappan, artist and printmaker extraordinary, and his eyes light up.

“Yes. Gödel, the mathematician. I knew him well because my older brother had introduced me to his work,” Palaniappan says, when we talk a little after the excitement of preparing for his retrospective, which opened in December 2024 at Chennai’s DakshinaChitra Heritage Museum, is behind him.

In her foreword to the exhibition catalogue, Deborah Thiagarajan, the founder and president of DakshinaChitra, writes: “Palaniappan’s works reflect a deep intellectual and emotional connection to the world around him, blending elements of science, psychology and abstraction and visual aesthetics.”

Rich and exhaustive catalogue

And, in fact, for those who might miss the superb show (“Mapping the Invisible: Retrospective show of Rm Palaniappan”, December 15, 2024-March 31, 2025), the Madras Craft Foundation has published a rich and exhaustive catalogue—more commemorative volume than catalogue—that reproduces his major oeuvre. The catalogue, designed by Palaniappan himself, is as much a work of art as his pieces hanging in the gallery and has an excellent opening essay by Sadanand Menon, Chennai-based writer and critic.

Titled Mapping the Invisible, the volume traces the Escher-like trajectory of Palaniappan’s life from the small town of Devakottai in Tamil Nadu’s Sivaganga district, close to Karaikudi in Chettinad, famous as the homeland of the enterprising and prosperous business community of the Nattukottai Chettiars.

Also Read | The printmaker’s palette: Gulammohammed Sheikh’s six-decade journey

The Nattukottai Chettiars travelled to different places of South-East Asia extending their skill as merchant bankers to different local communities. A striking feature of their lives was that they would always return to their ancestral homes each year, bringing with them, as Palaniappan recalls of his grandfather who went to Vietnam, mementos of their sojourns. Quite often, these objects were made in Europe, porcelain, glassware, enamelled metalware, and more. In a sense, the world came to Chettinad in the steel trunks of these adventurous businessmen.

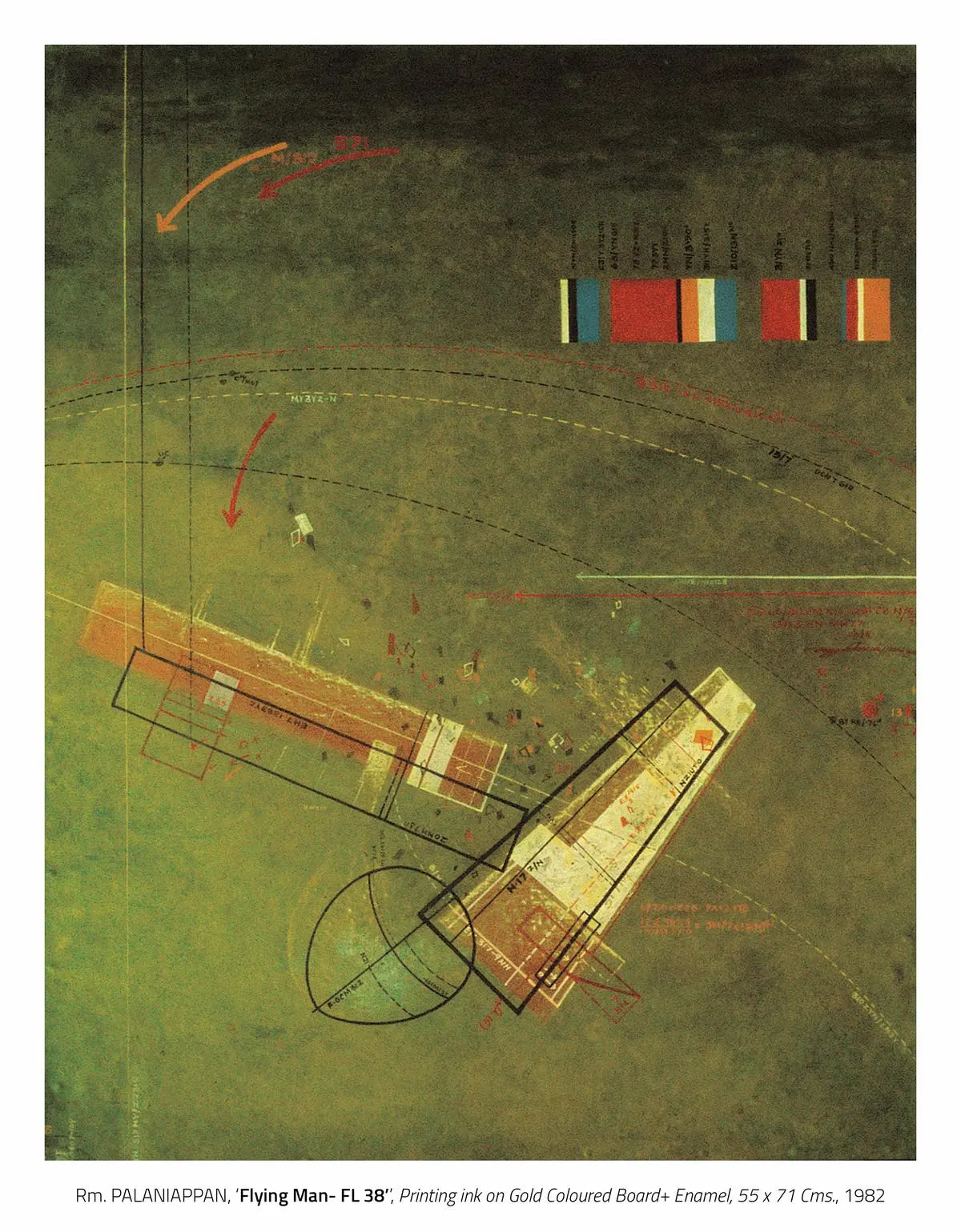

“Flying Man-FL 38”, 1982. Printing ink on gold-coloured board and enamel.

| Photo Credit:

DakshinaChitra Museum

Long before Palaniappan joined the Government College of Arts and Crafts, from where he graduated in 1981, he had been introduced to the Western world through photography and cinema. His early apprenticeship with his elder brother in the printing business edged him towards printmaking. One of his experiments in the genre was to scratch out the outlines of a German desk calendar and create an entirely different pattern of abstract forms by recalibrating the surface.

The idea of the accidental artist arriving at an inner imagery remains a preoccupation with Palaniappan when he voices what we might describe as his Error Manifesto. “The ERROR is the default of any ‘Action’; and one must accept its existence for peace and calm,” he writes in response to me when we talk of his work. “Human error is not separated from the universe; it is the natural outcome of the same laws that govern the cosmos. The perception of error is a localised human experience, shaped by our biological and psychological frameworks. When viewed through the lens of universal oneness, error is not a flaw but a part of the infinite process, contributing to the growth, complexity and the unfolding of existence.”

When looking at his immaculately wrought notations in print, what impresses the viewer is the precision with which he has achieved the image. It is the opposite of what he describes as “error”. Menon describes in his essay how a chance viewing of a 1945 Russian film, The Fall of Berlin, in Devakottai in his early years had a wholly different response from Palaniappan. It propelled his imagination into a new extraterrestrial dimension where he saw gravity defying/defining space. Or, as he is quoted as saying: “Only someone flying in space can make a three-dimensional drawing and stretch it to infinity—thus expressing complete freedom.”

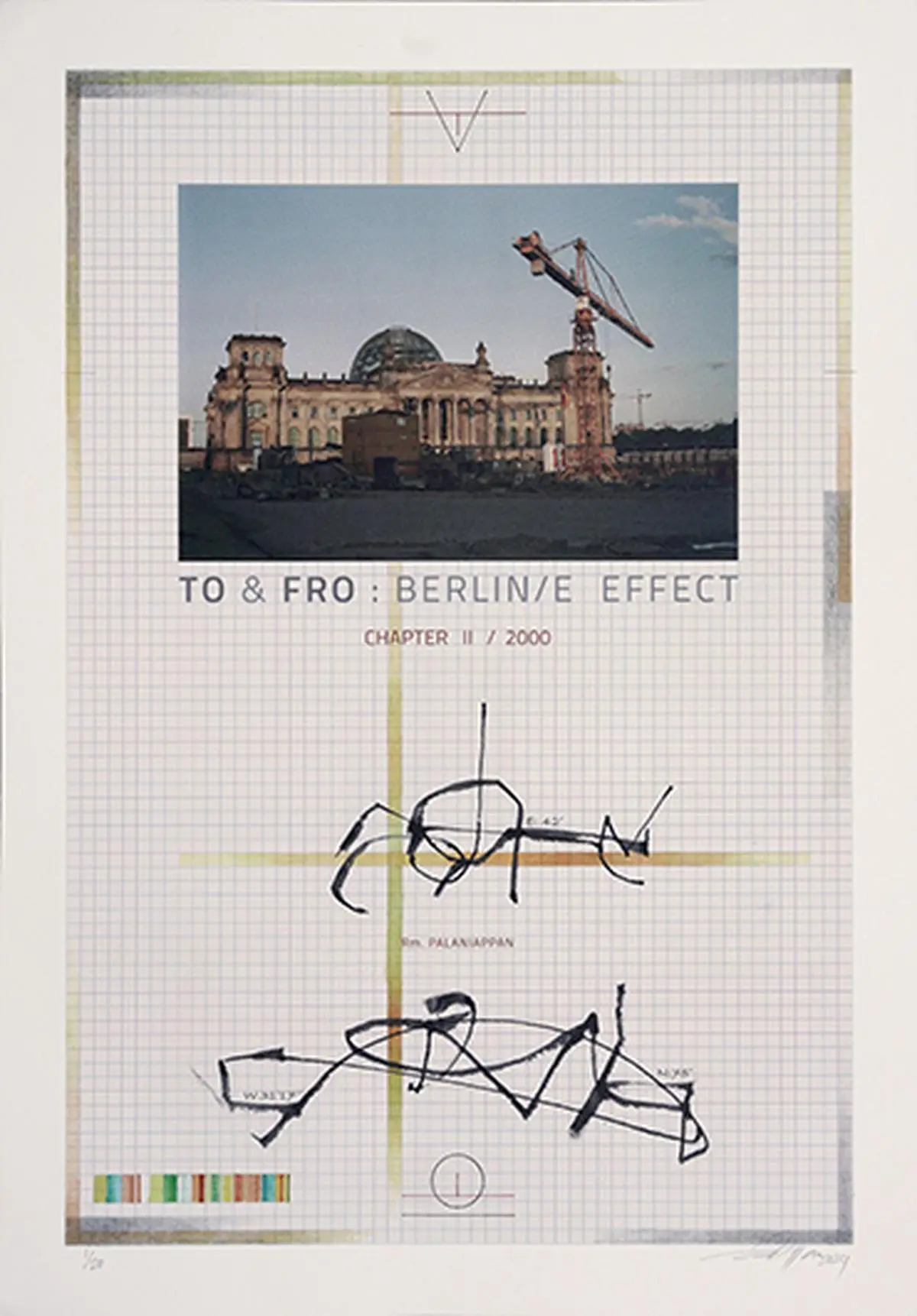

Many years later, when he was actually in Berlin, he produced his Berlin series, which traces the many steps with which he explored the salient landmarks of the city. It documents and memorialises his physical and imaginative response to Berlin, a city that had resonated so long in his memory.

Passion for perfection

Much later, in 1996, during a stint in Oxford, the artist describes how he was going through a phase of computer-aided art. “I would walk through various prefectures of Oxford in the evenings and spend time in the library till midnight. While doing my daily sketches, I would tint the pages of my notebook before drawing on them. Often, I continuously sketched and painted across four or five pages. As this exercise progressed, I noticed that each roughly tinted colour, applied with free strokes on every page, carried its own specific emotion. I also noticed that, in some way, the colours had a connection to Oxford and its environment.”

Palaniappan was the Secretary of the Lalit Kala Akademi in Chennai for 20 years (1997-2017), but during that time, he was also engaged in initiating artists into printmaking. According to Manjula Padmanabhan, an illustrator and graphic artist, his mentoring was very precise, and he was wholly taken up with a passion for perfection in the process of printmaking. A passion that continues to animate him and spills over infectiously when one speaks to him of his work.

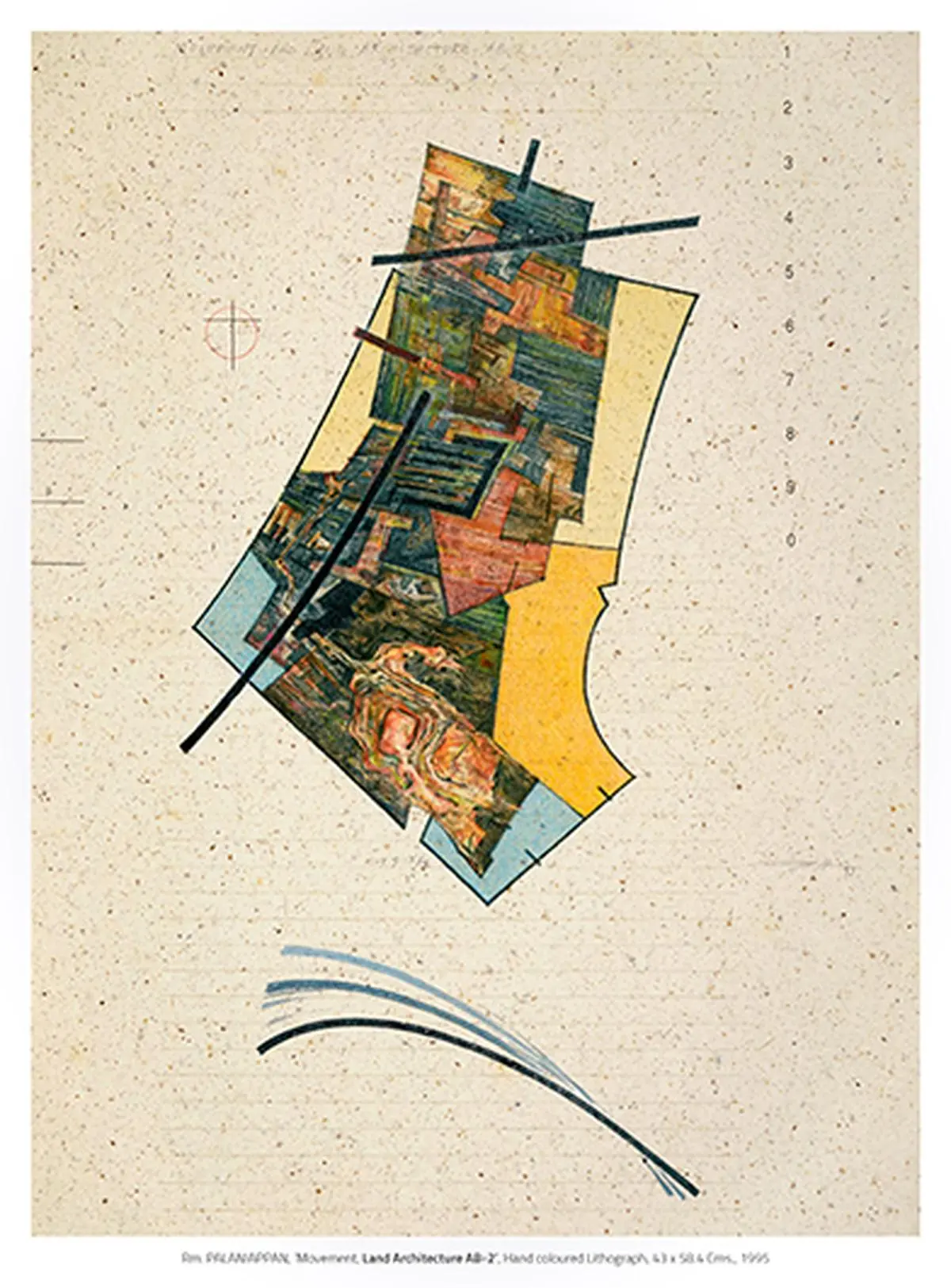

“Movement Land Architecture AB-2,” 1995. Hand-coloured lithograph.

| Photo Credit:

DakshinaChitra Museum

The years when Palaniappan was evolving as an artist were a time when some seminal ideas were sprouting in the otherwise conservative city of Chennai. The dancer-choreographer Chandralekha was paying a tribute in dance to the mathematical genius of Bhaskara II’s Sanskrit text Lilavati; Deborah Thiagarajan was using her anthropological vision to preserve south India’s architectural heritage in DakshinaChitra; and the then Cholamandal-based artist Viswanadhan was exploring the four elements in film—Earth: Fire: Water: Air. It is no surprise that Palaniappan took off from this creative springboard and drew upon architecture, aeronautics, engineering, and cartography as inspiration for his art.

The full title of Douglas Hofstadter’s book is Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, and he presents in it a view of space and time through the eyes of three very different individuals. Kurt Gödel was a logician and mathematician exploring the world through numbers; M.C. Escher’s work as an artist uses black upon white forms in repetitive sequences to suggest different dimensions; while John Sebastian Bach, the deeply contemplative musician, composes music using sounds mathematically as though hearing another refrain through the music of the spheres.

Foundational ideas

The concept of negative and positive values, whether in space, or in numbers, or patterns of sound, or matter has long been a foundational idea in Asian notions of the world. They might be depicted as opposing forces of male and female, light and dark, or “ying-yang”, or “Ananta”, whose symbol in Sanskrit is “8”, or endless coil, suggesting ever spiralling numbers from zero to infinity.

From the Berlin series.

| Photo Credit:

DakshinaChitra Museum

In response to a question posed by Vaishnavi Ramanathan, art critic and curator based in Cincinnati in the US, in an interview published in the same volume, Palaniappan explains his vision. “In essence, art—like music—is a continuous process of searching for the dimensions of energy that guide us beyond our immediate sensibilities. This journey, whether through sound, or line, or form, is about exploring the unseen forces that shape and direct our perception of the world.”

In his life and work, Palaniappan has woven a unique golden braid of many strands, some complex, some austere, that come together in a body of work that is as challenging as it is fulfilling.

Geeta Doctor is a Chennai-based writer, critic, and cultural commentator.