Tegan Voisey, an Inuk artist from Makkovik, is using the jewellery she makes to express her individuality and connection to her culture, as well as to uplift her community.

Article content

Indigenous cultural representation and revitalization comes in many different shapes and forms. Varying skill sets can be drawn upon to uplift a culture and community.

The arts can be powerful in its accessibility for a larger audience to observe and gain a better understanding of a different viewpoint or perspective, and to support different Indigenous artists and communities.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Tegan Voisey, an Inuk artist from Makkovik, is using the jewellery she makes to express her individuality and connection to her culture, as well as to uplift her community.

Voisey moved out of the North Coast of Labrador when she was about a year-and-a-half old, and has lived all across the country since then. She now resides in Alberta.

But while she no longer lives in Labrador, she visits as often as she can, and the influence of her birthplace can be seen in her business.

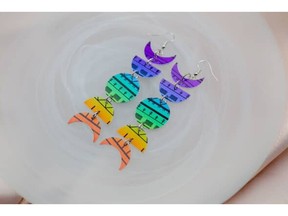

Through her business, The Littlest Inuksuk Inc., Voisey sells earrings that present her culture while also showcasing her personal style.

“I like the big earrings,” she said.

“I like the things that are really sometimes more shocking or less like talked about, but it’s a way that I’m able to show myself. It’s a way that I’m able to show myself (and) present my culture.

“It’s from my viewpoint, almost.”

Finding herself through her art

It was in 2019 that Voisey first began creating earrings, and the business that eventually grew is nothing she could have imagined.

Advertisement 3

Article content

“I haven’t really taken the straight and narrow path to get where I am,” she said. “At one point, I was going to university and I was planning a career in social work because I’m very community-minded and focused. But it just wasn’t the right timing, and it wasn’t right for me.”

At the time, she was feeling very lost, but has since found herself through her art in a way that she has never been able to before.

“I don’t know if it’s my forever plan, but I’m following my passions,” she said.

While on maternity leave in 2019, she began exploring jewellery-making as a hobby. It was her mother who had instigated the idea as she’s very into arts and crafts, explained Voisey.

“It quickly became a daily part of my life,” she explained. “So, over time, I increased the amount of mediums that I’ve worked with and just like to really explore different things.

“So, now, it’s basically my life.”

Pride in her culture and identity

Right from the beginning, Voisey took inspiration from her cultural heritage for her jewellery. It only made sense, as her culture has always been a very significant part of her life.

Advertisement 4

Article content

“I really love my hometown. I love the North Coast. It’s a big part of who I am. My identity, and cultural pride, has always been something that I’ve felt,” she explained.

“It makes me really happy to be able to create things to help other people feel that same pride.”

Significant milestones

Since starting the business in 2020, Voisey has had many memorable moments and three significant milestones to date.

Her first time participating in a project for public consumption and at a grand scale was for the Inuit Nunangat toonie released by the Royal Canadian Mint in 2024.

“A very significant piece of my journey,” she said. “A lot of my projects were really small, and like, I do a lot of my selling through social media, it’s more private. So that was a really cool and exciting opportunity that I was able to work on. I’m really grateful for that.”

She has also participated in the Adäka Cultural Festival in Yukon. It was the first event she attended for her art.

“Just to be among other artists of such high caliber, it was really an honour for me,” she said.

Advertisement 5

Article content

Advertisement 6

Article content

Featured in North of North

More recently, Voisey’s pieces have been worn by Anna Lambe on the television series North of North, as well as Lily Gladstone.

Voisey knew production had purchased some of her earrings, but there was no guarantee that they would be featured or how they would be featured.

It wasn’t until the show aired and she saw Lambe wearing the pieces that Voisey found out.

“I would have watched the show regardless, but it was really exciting to see how many times they were featured and that they were so prominent,” she said.

“Netflix used a still shot of one of the times where she was wearing them in some of their promos and stuff. So that was really big for me.”

Advertisement 7

Article content

‘A life-changing moment’

The show itself was such an exciting and proud moment for her community, she added, and featured so many Inuit designers.

“It felt so cool to be a part of something that was so big,” she said. “And not big in the fact, like, oh, Netflix and TV or whatever, but so meaningful.

“It was really a moment where we felt represented, and then to have our artwork represented in that same way, it felt like a life-changing moment just because of that immense pride, you know?”

Cultural appropriation

Can non-Indigenous people purchase and wear jewellery that is inspired by Indigenous culture?

Cultural appropriation is an important topic when discussing art and jewellery that takes inspiration from a particular culture.

What’s important to note, said Voisey, is that the recreation of Indigenous cultural designs for monetary gain is wrong.

“I know that some people just don’t want you to recreate at all, and then I think a lot of us are just like, if you make something for yourself, OK, but if you’re making it and posting it and selling it, that’s like a whole other thing,” she explained.

Advertisement 8

Article content

To purchase Indigenous art and jewellery from an artist you know to be Indigenous as a non-Indigenous individual is entirely different, she said. It’s supporting the community.

“For the most part, most Indigenous artists that I know appreciate support from anybody. Like, you can wear our work, it honours us, it honours our culture. You can buy it and wear it and gift it. There’s no disrespect in that whatsoever,” she said.

“We really appreciate the support. It puts money into our communities. Where the line is, is recreating for profit, I think, is the biggest thing. There’s so many things in our culture that are like being renewed and are important to us, but we haven’t been always able to practice those elements in our culture and to see them taken and then used, it feels very exploitative.”

Art as an educational tool

The accessibility of art can be an educational tool. The more culturally significant pieces are shared, the more understanding is created in the wider public.

Advertisement 9

Article content

This is a major driving factor for Innu artist Agathe Aster from Sheshatshui. Aster first began painting about eight years ago and was taught by the late Innu artist Patrick Nuke.

“He’s the one that got me into painting. He’s the one that taught me how to paint. Sadly, he passed away a year ago,” she said.

After completing a mural in her room, Aster was invited to paint a building; she has since painted two murals and two buildings in her community.

The decision to begin selling some of her work outside of her community stemmed from a desire to introduce more people to her culture.

“I wanted more people to know more about my culture and have my art being seen by people,” she explained.

‘I only paint what I’ve seen’

A significant inspiration for her work is the connection that the Innu have to the land and its animals.

Aster had previously spent four years as a wilderness guide and would draw on landscapes she would see and experiences she would have.

Another heavy influence on her work has been her grandmother; hearing stories of how the land used to look and feel.

Advertisement 10

Article content

“I only paint what I’ve seen and what I’ve heard from the stories from my grandmother,” she explained.

She paints moccasins and other traditional elements of her culture.

Teaching the younger generation

Imbuing her community’s cultural traditions in her work is a way of contributing to the continued revitalization of her culture and language.

“A lot of the new generation in my community don’t speak our language anymore,” she explained. “Usually, all the kids in the community speak English, and they don’t know much about it. So I want them to see what the culture is about, so they could learn more about it.”

Aster recently visited the area where her grandmother was born for the first time in many years, bringing her son with her.

“She’ll be 80 this November, so this is really exciting, and I haven’t been here since I was six, so it’s my first time being out here again,” she said.

“It is really beautiful out here and I ended up taking my son, who’s eight, and he likes it out here. It’s the first time he’s been out of the community and going on the helicopter.”

Advertisement 11

Article content

Having her son with her was an important step to introduce him to the land, animals, and his ancestors’ traditions, she explained.

“It’s really exciting,” she said.

Read More

‘Believing in yourself’

With kids of her own, Voisey’s advice for any young Indigenous women who may be looking to start their business or enter into the arts world is simple.

“Sometimes you have to work at it, even when it feels like there’s nobody there supporting you,” she said.

“Sometimes, there’s gonna be times where you’re going to need people to make you feel like what you’re doing matters and that you’re doing well and getting better.

“But as long as you stick to believing in yourself, time passes and you get through it.”

Anasophie Vallée is a Local Journalism Initiative reporter covering Indigenous and rural issues.

Article content