In the rarefied space of Métiers d’Art watches and high jewellery, centuries-old decorative techniques are preserved and brought to life. Vacheron Constantin, Piaget, Cartier and L’École School of Jewellery Arts are committed to honouring these traditions.

There’s an awe and elegance enveloping high jewellery and Métiers d’Art watches, which is rarely seen and experienced with other luxury goods. While powerful storytelling and an air of exclusivity brilliantly package these beautiful objects and intensify their appeal, what makes them truly special are the meticulous focus on highly specialised crafts and techniques – many centuries old – their limited if not unique production and the fact that months, if not years, were spent on their completion.

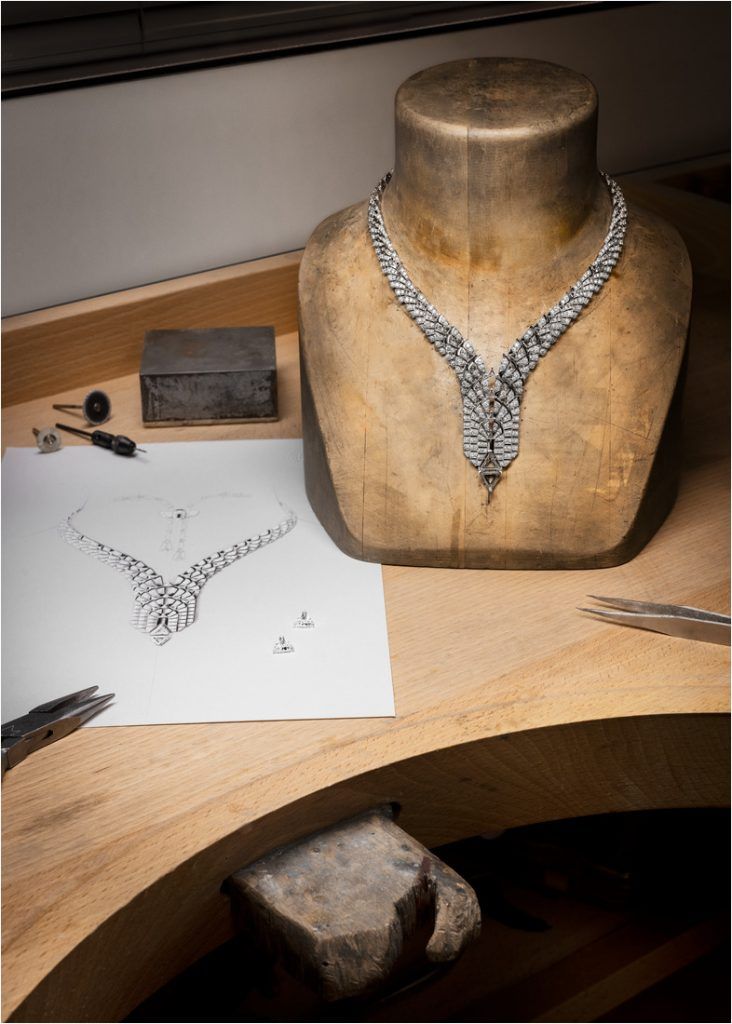

When encountering these exquisite creations, we feel compelled to scrutinise them through different lenses: as mechanical marvels, finely crafted objects, stunning assemblages of gemstones set in precious metals and

even as miniature artworks. Sometimes they can be all of these.

Through these tour de force pieces, brands are able to demonstrate their artistic and technical capabilities – and, indeed very deep pockets. Throughout the year, they host exclusive events for which no expense is spared, with concepts as awe-inspiring as they’re pretty damn wild – think extravaganzas in ancient French castles, Italian villas and chartered helicopter rides – to unveil pieces many years in the making. Such grandeur is fitting; pieces such as these deserve a grand introduction. But behind all the spectacle, they are, at their core, true works of art.

Craft Savant

One brand especially noted for creating pieces of masterful technique and artistry is Vacheron Constantin. In fact, the watch manufacture has an entire collection focused solely on its craftsmanship and artistic ambitions – rather aptly, it’s called the Métiers d’Art series. Here, homage is paid to ancient Chinese culture in dial canvases, on which master engravers, enamellers and artisans work their magic. Under the loupe, the work is astounding.

Vacheron Constantin’s style and heritage director, Christian Selmoni, describes the Métiers d’Art collection as a culmination of expertise passed down through generations. “The maison’s artisans are masters of rare and intricate techniques, requiring years of training and a deep understanding of both traditional craftsmanship and modern precision, resulting in pieces that are not only functional but also timeless works of art,” he says.

He’s quick to add, however, that these craftsmen not only preserve age-old techniques, but also innovate. “These undertakings demand an intimate understanding of materials, meticulous attention to detail and a commitment to creating pieces that transcend time,” Selmoni says. “Craftsmanship is more than a skill; it’s a philosophy of excellence, where every component is thoughtfully designed, hand-finished, and assembled.”

One of the rare crafts encompassed by métiers d’art is enamelling, seen predominantly on artistic dials. Grand feu, an enamelling technique, involves applying multiple layers of crushed pigments to a metal surface, typically a watch face. Each layer is carefully applied and fired, sometimes up to 30 times, and leaves little to no room for error. We see this artistry in Vacheron Constantin’s Métiers d’Art Tribute to Great Civilisations, developed by the maison in partnership with curators at le Louvre.

Focusing on specific historical eras, such as the Persian Empire of Darius I, ancient Egypt during the pharaohs, Hellenistic Greece after Alexander the Great and imperial Rome – each represented by an artefact in le Louvre – Vacheron Constantin reproduced these epochs through miniature sculpted appliqués in gold. “Each era is revealed through sub-dials engraved with motifs from the decorative arts of the time,” Selmoni says. “The self-winding 2460 G4/2 calibre, with its unique construction, allows for creative expression and masterful compositions, displaying time and calendar indications through discs, while leaving ample space on the watch face for our crafts.” These engravings are further enhanced by guilloche – the meticulous engraving of repetitive patterns using century-old machines – and gem-setting, which requires both technical skill and sophisticated aesthetic judgment.

Engraving is another technique often seen in high watchmaking, which is given an exceptional range of expression as it can be presented on cases, dials and even the small components of a movement, where engravings are carried out to the nearest tenth of a millimetre.

Occupying what’s arguably the pinnacle of exclusivity within the Vacheron Constantin universe is Les Cabinotiers, a department dedicated to making unique and bespoke pieces, rooted in the tradition of 18th-century Geneva, where European dignitaries commissioned their timepieces directly from the cabinotiers. Artisans in this workshop often spend months, if not years, on a single creation, working tirelessly to bring their clients’ dream watches to life. A remarkable example from this department is Les Cabinotiers Westminster Sonnerie – Tribute to Johannes Vermeer Pocket Watch, whose case is engraved with acanthus leaves, tulips, and “pearl” decoration, its dial in grand feu enamel features an enamel miniature of Vermeer’s Girl With A Pearl Earring by Anita Porchet.

While traditional crafts – also known as “historical” decorative arts, such as grand feu enamelling, hand- engraving, guilloche and gem-setting – are central to its Métiers d’Art workshops, in the name of accuracy and durability, Vacheron Constantin recognises the importance of incorporating advanced technology that includes CAD and precision manufacturing, in its processes. An example of this innovative approach is the Grand Lady Kalla high-jewellery timepiece, which features an easy-swapping system that allows the watch to be effortlessly converted from a wristwatch to a necklace. Vacheron Constantin also takes its commitment to art and culture beyond the confines of its workshops. As well as working with le Louvre, Selmoni highlights a memorable 2007 collaboration in which the brand partnered with the Barbier Mueller Museum of Primitive Arts to develop the Métiers d’Art The Mask edition.

Gold Standard

In the late 1950s, Piaget made the pivotal decision exclusively to use precious metals, particularly gold, which led to innovative concepts, such as carving gold and introducing colour through ornamental stone dials. “This way of thinking opened up a new world for the maison, and making jewellery and watches out of gold is the beauty and singularity of Piaget,” says Piaget’s creative director Stéphanie Sivrière. “We often say that mastery ignited artistry; it certainly unleashed a new creative flow.”

One of Piaget’s hallmark techniques, Decor Palace, emerged in the 1960s and became a defining feature of the brand’s goldwork. Inspired by guilloché and traditionally used for watch dials, it was groundbreaking for the time, departing from the customary smooth and polished surfaces, and introducing textured, rhythmic engravings. Rather than acting as a mere “supporting act” to gemstones, the Decor Palace technique elevated gold to centre stage.

“Interestingly, Decor Palace was just one of more than a hundred gold engraving techniques,” Sivrière notes. Initially unnamed, these patterns were categorised by codenames, such as A6 or B2. In the early 2000s, Sivrière studied the maison’s heritage and aesthetic history, and was captivated by the horizontal lines of Decor Palace. She began applying this technique not only to watches but also jewellery, making it a prominent feature in its Limelight Gala watches, Possession pieces and high- jewellery collections.

While these traditional techniques lend a distinct quality to Piaget’s pieces, Sivrière emphasises the importance of innovation. “We’re continuously rediscovering and reinventing techniques, including some chain methods that had fallen into obscurity,” she says. “This is what makes the design and development process so fascinating.” That innovative approach was integral to the revival of the Piaget Polo 79, which she describes as “the same but different”, blurring the lines between a watch bracelet and a bracelet watch. Made from solid gold, the case and bracelet of the Piaget Polo 79 are seamlessly integrated, creating the illusion that the watch was forged from a single piece of the precious metal. In true Piaget fashion, artisans play with texture, contrasting the highly polished gadroons with the satin-brushed finish of the links.

Beyond exceptional goldsmithing, Piaget displays the breadth and depth of its metiers d’art in an orange carnelian necklace from the recently launched High Jewellery 150th Collection. “In high jewellery, maisons often try to conceal the structure with an abundance of gemstones,” Sivrière says. “But this necklace is flamboyant yet wearable and distinctive, with the stones being just as important as the hand-woven gold mesh that shines against the skin.”

Piaget is committed to preserving these crafts for future generations while keeping customers educated and engaged in the artistry behind its exquisite pieces. “These centuries-old techniques are tirelessly taught to our apprentices to make sure they’re not lost,” says Sivrière. “At the same time, we strive for transparency, explaining these techniques to the public in an engaging manner through storytelling.”

Building a Legacy

In 2014 in the small Swiss city of La Chaux-de-Fonds, Cartier founded the Maison des Métiers d’Art, an institution whose sole purpose is to preserve, innovate and transmit métiers d’arts. There, ancestral techniques such as enamelling, Etruscan granulation, filigree and marquetry are safeguarded and taught. Given that such crafts are traditionally passed down from master to apprentice orally and through hands-on experience, the 50 artisans and engineers working there focus not only on proper documentation but also on rediscovering and adapting historical practices, techniques and tools to modern methods.

The maison also works closely with schools in Switzerland and France to ensure these crafts are taught to the next generation of artisans. Master craftsmen are also routinely invited to work on specific creations with specialised teams in other areas, creating a synergy and ecosystem that encourages that shared desire for excellence and ingenuity.

Within the Maison des Métiers d’Art, a team of engineers, experts and technicians develops technologies related to microfluidics, mechanics and magnetism. They explore how contemporary innovations, such as 3D printing on gold

or laser techniques, can be integrated with centuries-old practices. This collaborative effort has resulted in more than 30 patents.

According to Karim Drici, manufacturing director at Cartier, “The spirit of this place is unique: preserving and sharing artistic crafts that are often forgotten or rarely practised, all within a dynamic in which innovation plays a vital role in fuelling the maison’s boundless creativity. We believe this dialogue between tradition and modernity will empower these artistic crafts to endure and remain vibrant for years to come.”

Transmission of the Arts

Another institution dedicated to the transmission of knowledge is L’École School of Jewelry Arts, founded more than

10 years ago with the support of Van Cleef & Arpels. The school offers courses in three major fields: the history of jewellery, the world of gemstones and the savoir-faire of jewellery-making techniques, all taught by art historians, gemmologists, jewellers and artisans. Olivier Segura, L’École’s managing director, notes that jewellery know-how

is as much about tradition as modernity.

“Some tools have been used for centuries without any modification, but others have been developed to this day for the comfort of craftsmen and to allow achievements that were previously impossible,” he says. “The transmission of knowledge and know-how is most often done from master to student, which ensures the sustainability of gestures and tools. However, it’s true that when we look further back in time and history, some knowledge has been lost, and it’s sometimes impossible for contemporary jewellers to reproduce certain very old jewels.” To address this, L’École has initiated several research projects in partnership with jewellers and universities, aimed at understanding and recreating these lost techniques. For example, the investigation of a gold necklace dating to 300BCE, which was discovered in France and has long remained an enigma for researchers and jewellers.

“Our mission is unique,” Segura says. “We aim to raise awareness of the jewellery arts among diverse audiences, from children to professionals and researchers. This mission is crucial, because jewellery and ornamentation represent the earliest arts developed by humankind. They unite us across cultures – from East to West and North to South – connecting us in our appreciation for the beauty of nature and the craftsmanship perfected over time.”

The information in this article is accurate as of the date of publication.