Every other year, the Kingston Prize celebrates the best in Canadian portrait art. Its newest champion was revealed Nov. 14; Madonna in a Tulip Chair by Louise Kermode was declared the winner of the 2025 competition at a private reception in Toronto. Jurors selected the photorealistic oil painting from 30 finalists, and Kermode, an artist from Waterloo, Ont., received $25,000 in prize money.

Kermode, 61, is a former undergraduate assistant who retired from the University of Toronto last year. She now pursues her art practice full time, and in her Kingston Prize-winning piece, she portrays a woman in her 70s whose self-assured presence fills the frame.

In the painting, the subject’s eyes lock on the viewer. With her head held high, she sits in a mid-century modern swivel chair. Her open-armed posture appears relaxed and welcoming, suggesting the draped silhouette of a Virgin Mary figurine. Is this woman expecting your company, or awaiting devotion from the faithful? Whatever the case, in her printed capris and a loose pink blouse, she could be any contemporary woman her age.

If she seems especially familiar, though, that’s not the reason why. The model’s name is Donna Meaney, and you’ve seen her in a painting before.

When she was younger, she modelled for Mary and Christopher Pratt

Kermode has described Meaney as “Canadian art royalty, having posed in her youth for two titans of Canadian painting, Mary and Christopher Pratt.” Among Canada’s best loved realist painters, the couple first crossed paths with Meaney in 1969, when she was still a girl in high school.

Mary’s work was beginning to attract attention around that period, and with four kids at home, the Pratts hired Meaney, who was then 16, to be their nanny and housekeeper. She lived with the family for three years, and while working there, she began to model for Christopher.

During that period, Christopher had sex with Meaney, and according to biographers, Mary was soon aware of the situation. Nearly a decade later, she would make Meaney the subject of one of her paintings.

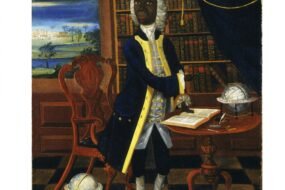

At some point in the 1970s, after Meaney’s departure from the Pratt house, Christopher gave Mary photographic slides to paint from. They were pictures he’d taken of Meaney years ago. One of those images, a seated nude pose, would inspire the first of Mary’s Donna paintings: Girl in Wicker Chair.

The artist died in 2018, and today, as in her lifetime, she’s celebrated for her still-life paintings of everyday subjects — jars of jelly, fish filets and dirty dishes — which she captured with an almost lurid, gem-like radiance. But when it comes to painting people, Mary depicted Meaney more than any other figure, and would eventually work from photos she took herself.

Mary stayed in contact with Meaney, and in an Art Canada Institute biography, she’s quoted describing their relationship as something closer to family than friendship. Still, there’s a destabilizing quality to Girl in Wicker Chair. Even with her knees pulled up to her chin in a protective pose, the figure appears shockingly exposed. Who dares to look at her and why?

According to biographer Carol Bishop-Gwyn, author of Rivals in Art: The Marriage of Mary and Christopher Pratt, the couple’s professional relationship could be adversarial; “Painting Donna, the young mistress, thus became part of the competition,” she writes in her 2019 book. “The artistic battlefield would be the body of the very woman who had usurped Mary in her husband’s erotic imagination.”

Why revisit this moment in Canadian art history?

Kermode says she wanted to reference Girl in Wicker Chair through her portrait of Meaney. “Women are portrayed in a particular way so often — often through the male gaze. … And in Donna’s case, there was kind of a triple gaze there: Christopher took the photos and Mary painted from Christopher’s photos. And they had a complex kind of relationship between them that came out in the painting.”

The idea of revisiting a moment in Canadian art history — and “an art-historical muse” — compelled Kermode to paint the piece. She wanted to continue Meaney’s story, “but in a different way.” Says the artist: “I just thought it was a really rich subject that I could use all the skills that I’ve been training for.”

Still, the painting couldn’t have happened if she didn’t meet the woman herself.

It happened a year and a half ago. Kermode was still working at the U of T, and she and a friend from the art history department were having lunch at the Gallery Grill, a restaurant on the St. George campus. There, her colleague saw Meaney.

“I didn’t recognize her, initially,” says Kermode, but the friend suggested she ought to paint her. In recent years, she’d been building her skillset through classes at the Academy of Realist Art in Toronto, but had yet to really pursue a focused practice.

“[My colleague] had been trying to get me to paint seriously for awhile, and the light bulb just went off.” By the end of lunch, she’d asked Meaney for her phone number.

‘My painting is how I see her’

“I think Donna was a little bit reluctant, at first, because, you know, who am I?” says Kermode, who still doesn’t know for sure why Meaney agreed to the proposal. “I think she felt comfortable because I have a Newfoundland connection,” says the artist, whose father’s family is originally from the region.

Kermode invited Meaney to her home for a photo shoot, but before her arrival, the women spent an hour discussing how she’d be portrayed in the painting. Meaney’s only caveat was no nudes. “That was really the only limit she put on me,” and the artist was happy to oblige.

In the finished painting, Kermode sees a different sort of vulnerability — a feeling that represents her own lived experience. “She’s putting herself out there again,” says Kermode. “There’s a vulnerability to her being someone who is aging, which I resonate with.”

I see her as a strong, resilient person who’s gone through a lot in her life. There’s a maturity now that she didn’t have, of course, when Mary was painting her. And a dignity as well, that I hope comes across in the painting.– Louise Kermode, winner of the 2025 Kingston Prize

The painting’s symmetry and light is a nod to the work of both Mary and Christopher Pratt, the artist explains, but how does she see the relationship between this new work and the Donna paintings that came before? Is it a reaction, a reference, an homage?

“It’s all of those things, weirdly,” says Kermode. “I can’t ignore the fact that there’s a complex history there. … I can only put on the canvas what she shows me and what I get from her. My painting is how I see her.

“I see her as a strong, resilient person who’s gone through a lot in her life. There’s a maturity now that she didn’t have, of course, when Mary was painting her. And a dignity as well, that I hope comes across in the painting.”

Meaney joined Kermode at the Kingston Prize reception on Friday, and the win has been a surprising thrill. “I’m so grateful,” says Kermode. “It’s a huge boost. Not only financially, it is a huge boost visibility-wise.”

She’s already working on her next painting, she says. It will be a new portrait of Meaney.