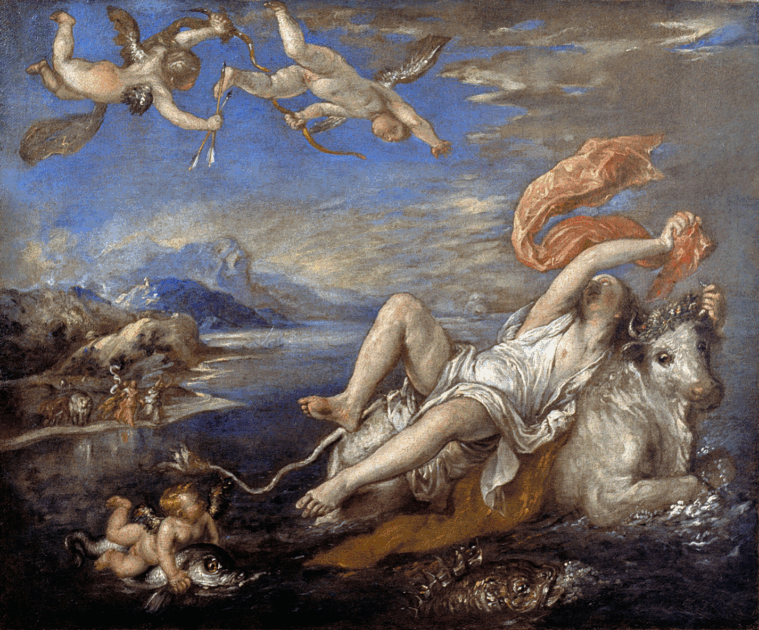

Titian: The Rape of Europa, 1559–62; in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

A philosopher interested in public life can learn from how the popular media handle issues of art and morality. I read with interest now and then Slipped Disc, a web site devoted to gossip about the music world. Recently they posted a discussion about a Mozart performance under the heading, “This is what you’ll receive if you want to see Marriage of Figaro at Glyndebourne Festival Opera”. The advisory statement warned potential spectators that the opera presented unwanted sexual advances and aggressive behavior. (Read it for yourself, it’s on-line.) True enough, but you don’t need to have studied musicology to know that. A glance at Wikipedia will suffice. What interested me, however, was that the responses on-line ridiculed this statement. Marriage of Figaro is a great opera set in the old regime, several people said, and so why would anyone need to be warned about the morality of the story? You might as well complain, I suppose, that Rossini’s operas about Islam reveals him to be an Orientalist.

Here, I believe, we actually face a very interesting issue, which deserves reflection. To what extent are we justified in looking critically at the moral issues presented by an artistic masterpiece from an earlier era? I am asking: should we judge that work by our standards, or — rather— might we not admit that it is of an earlier time, when different ways of thinking were prevalent? It happens that in my own present research, devoted to the history of painting in Venice, that a very challenging, conceptually comparable case has recently been discussed. And this example deserves attention because I can here present a good reproduction to accompany my discussion.

Titian painted in late middle-career, in the 1550s and 60s, a series of Ovidian pictures for a grand patron, the Spanish king. These works were exported directly, and never shown in Venice. Recently, however, there was a display of all seven first in London. And that show was much commented on. The picture that I will focus on is Rape of Europa (1560-62), normally on display at the Gardner Museum. Purchased by the founder, Isabella Stewart Gardner, it is generally acknowledge to be the greatest Italian painting in America. I will focus on this one work, while noting that some of the other works in this show revealed quite different erotic concerns. In Death of Actaeon (1556-9), for example, Actaeon is torn to bits by his hunting dogs because he inadvertently saw the goddess Diana bathing nude.

In Titian’s Rape of Europa we see Europe on the body of the bull, who is carrying her away. And she, hanging on for dear life is positioned to be frontally visible by the viewer. What do we make of the fact that Gardner installed this painting, which she adored, with one of her petticoats on the wall? Perhaps I can explain what looks problematic by contrasting a small, very little known work by a female artist. Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757), one of the most famous painters of her time, was greatly admired by prestigious collectors, both in the Venetian Republic and abroad, including French and Habsburg royalty. And by Antoine Watteau, whose portrait she painted. A long lived, very successful independent artist, she did not have the advantage of being the daughter of a painter, as did Giulia Lama, another 18th-century Venetian woman whose work now attracts attention. Her Rape of Europa (54-5) a small work painted on ivory, cannot legitimately be compared to Titian’s famous masterpiece which has been much discussed. And yet, it’s worth comparing her later version of this scene, which reveals her perspective as a woman. Where Titian erotically plays to the spectator, gives us a frontal view of the turned body of the lightly clothed Europa, Carriera shows her embracing a woman, with the bull looking a little cowed. Her Europa looks slightly melancholy. Carriera worked on a small scale, doing no frescoes or altarpieces, but she was emphatically not a modest artist.

The question raised by Titian’s picture are similar in form to those posed by The Marriage of Figaro. Once upon a time, formalist art historians claimed that we could appreciate a visual artwork regardless of its obvious content. That’s emphatically not possible before Rape of Europa, in which the subject is obvious and ambiguous. (Nor is it possible at The Marriage of Figaro, when the count’s desires are central to the plot.) That Carriera offers an alternative view only emphasizes that point. The question I pose then is: how do we deal with this Titian painting or, to go back to my earlier discussion, with Mozart’s opera?

Often in morality, so everyone knows, compromise is called for. A legitimate defensive war may cause, alas, innocent deaths. Still, on balance, we may decide to go to war. But it’s not clear how to understand compromise in this case. Titian’s painting is beautiful; and Mozart’s music is beautiful: but the subjects they present are morally dreadful. (Does it help knowing that Figaro outsmarts the count?) In these cases, it’s hard to imagine how compromise is possible. One might as well say, crime is wrong but you have done a magnificent mugging. This is why, in my considered judgment, the people who ridiculed the Glyndebourne handout missed the point. But I say that without myself being decisive. I greatly admire Marriage of Figuro and Titian’s Rape of Europe. And I see the problems here without any view of a convincing solution. What is to be done when our sensibility is divided in this way? Judging culture can be difficult!

NOTE

See the exhibition catalogues: Mathias Wivel (and other authors), Titian. Love-Desire-Death (London: National Gallery, 2020) and Alberto Craievich, Rosalba Carrera (Venice, 2023).