Sanwei Mountain in Dunhuang, Gansu Province Photo: Courtesy of Wang Yalin

Editor’s Note:

The Yellow River, which began to form 1.25 million years ago, gave birth to the roots and soul of the Chinese nation. As it meanders through nine provinces and autonomous regions, the river has not only shaped breathtaking natural landscapes but also nurtured the core wisdom and cultural richness of the nation. The intangible cultural heritages that have developed along the Yellow River – ranging from the Regong arts of Qinghai Province to the Weifang kite-making techniques of Shandong Province – serve as compelling evidence. In this series, the Global Times culture desk will guide readers through China’s most celebrated traditions that have flourished alongside the river, offering a glimpse into the pure essence of Chinese culture and how it continues nourishing contemporary life.

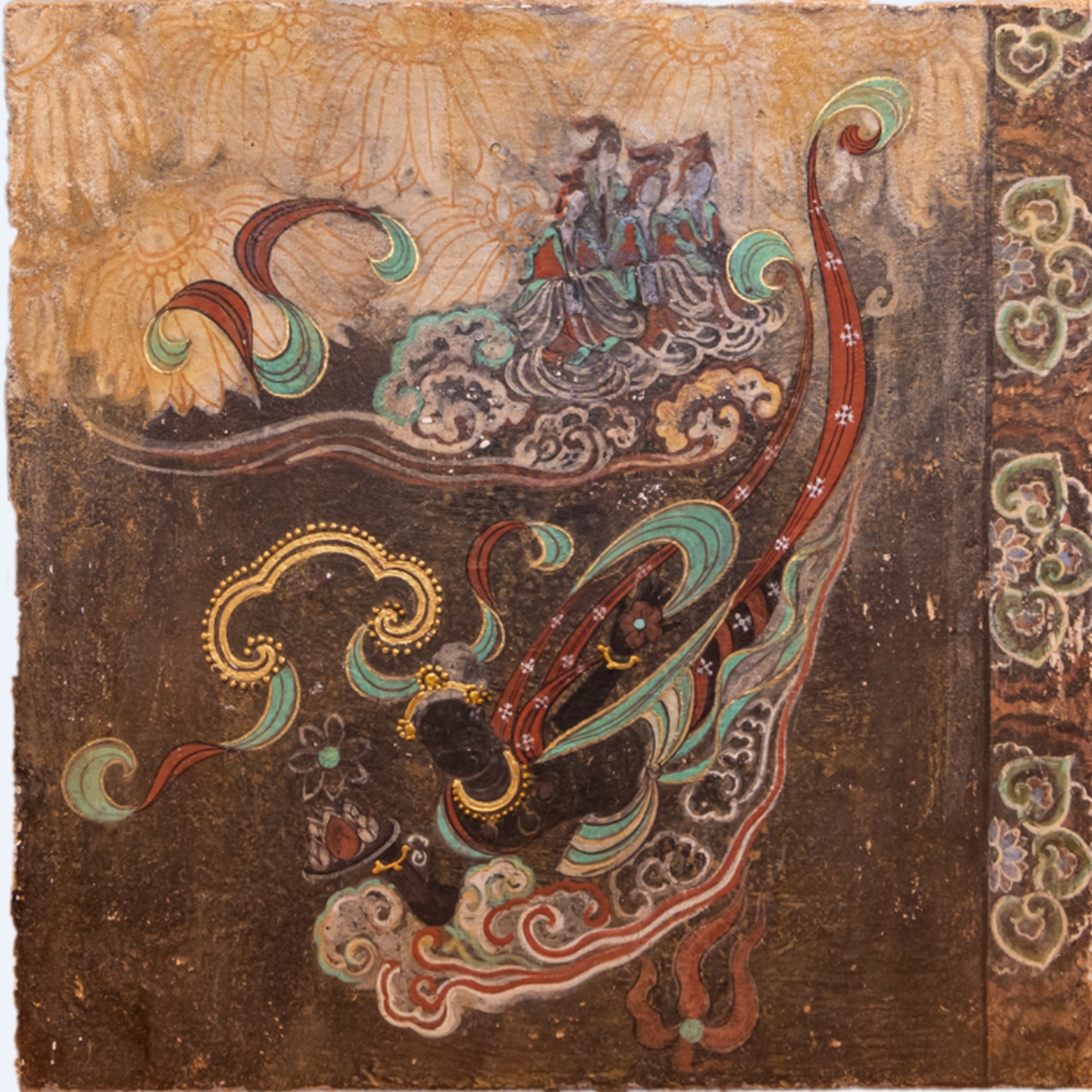

Wang Yalin, a fourth-generation inheritor of the Dunhuang stone powder painting technique, reproduces the Feitian murals of Dunhuang. Photo: Courtesy of Wang Yalin

In early winter, the usually crowded Mogao Caves fall into quiet. The desert winds sweep over the bare slopes of Sanwei Mountain, stirring dust from the sandstone cliffs. For Wang Yalin, this season is a rare gift that he described as “the best time to study the murals, and the best time to paint.” Each day at 6 am, she leads her small team into the mountains to collect the raw minerals that will later become the vibrant colors of the murals of Dunhuang.

The palette is deceptively simple: blue, red, white, black and yellow. These are the five mineral colors she calls the “colors of Dunhuang.” They are not just pigments, but are a living link to the land, to the Yellow River basin, and to a lineage of painters stretching back more than 1,000 years.

As a fourth-generation inheritor of Dunhuang stone powder painting, a provincial intangible cultural heritage from Northwest China’s Gansu Province inscribed in 2017, Wang grew up in Dunhuang and has learned Dunhuang mural painting art for nearly 40 years.

After all this time, she still prepares her pigments by hand, grinding azurite and malachite for blue and green, cinnabar for red, limestone for white, and soot or ochre for black and yellow. The mixture is painstakingly adjusted with animal glue to create a creamy consistency suitable for wall painting. Once applied, these colors harden into surfaces that glow like jewels, surviving the desert’s extremes.

“Every color comes from the earth itself,” Wang explained to the Global Times. “The pigments echo the Yellow River’s soil and reflect the natural world. They are tied to the ‘five elements’ of our Yellow River civilization: metal, wood, water, fire and earth.”

Echoes across the desert

Wang’s work is deeply rooted in Dunhuang, but these minerals resonates far beyond the local landscape.

The Dunhuang stone powder painting originated during the Han (206BC-AD220) and Jin (265-420) dynasties. It is a traditional mural painting method that integrates the Central Plains and Western Regions’ artistic techniques and is primarily used for decorating religious and residential buildings. The murals of the Mogao Grottoes – a UNESCO World Heritage site boasting rich collections of Buddhist artworks – in Dunhuang have an inseparable core connection with stone powder painting techniques, which is the most iconic technique for creating these murals, and the murals are the most splendid carrier of this ancient technique.

The technique leads to “stable colors that remain unchanged for 1,000 years.”

Wang has experimented with the same pigments in her studio, testing how they react to heat, light, and different binding materials. “The physical properties are unique. They have a texture and weight that make each stroke feel like it carries time itself. Grinding them is almost a ritual, it connects me with the artisans of 1,000 years ago.”

A stone powder painting by Hou Yanghong Photo: Courtesy of Hou Yanghong

Hou Yanghong, a painter and scholar from North China’s Shanxi Province who is also an inheritor of this intangible cultural heritage, said that her journey of learning Dunhuang stone powder painting, unlike Wang, is a story of seeking the origin of the artform. Hou came to Dunhuang as she “yearned to trace the lineage of Chinese painting further back, to its source.”

Hou still remembers how visitors from all around the world gazed at her when she showed the techniques at an artisan exchange conference. Her hands moved with practiced grace as she ground raw minerals with a stone pestle, sifting the resulting powder through fine silk before mixing it with adhesive to create pigments. The audience watched, entranced, as colors once hidden in stones emerged and bloomed across delicate rice paper, hues that have adorned the walls of the Mogao Caves for over 1,000 years.

“Dunhuang is not merely an isolated artistic outpost,” Hou told the Global Times. “It is a vibrant crossroads of the Silk Road, where minerals, motifs and ideas converged.” Some pigments Hou has used came from Guangdong and Hunan provinces, and even Afghanistan.

While Wang emphasizes local continuity – the colors of Sanwei Mountain, the mineral deposits of the nearby Loess Plateau – Hou highlights the geographical breadth and cosmopolitan spirit that these pigments embody. For her, Gansu is both a point on the Yellow River and a nexus of the Silk Road. The fusion of Central Plains traditions with influence from the Western Regions is visible not only in the materials but in the paintings themselves.

Early flying apsaras, typical images in the Dunhuang murals of celestial deities flying in the sky known as Feitian in Chinese, she noted, reflect Indian and Persian influences, which local artists gradually transformed into the elegantly robed immortals recognized today. “The evolution from naked celestial figures to robed immortals parallels a broader process of integration, where foreign elements are absorbed and reimagined within Chinese aesthetics,” Hou said.

This view is echoed by Neil Schmid, the one and only full-time foreign researcher at the Dunhuang Academy which administers the Mogao Grottoes. “The murals are a synthesis of artistic, cultural, and spiritual traditions from across Eurasia,” Schmid told the Global Times. “Central Asian dynamism, Indian compositional logic, Chinese linear precision, and mineral pigments from local sources all combine to create surfaces that still glow like jewels.”

The murals are also geographically and spiritually tied to the Yellow River, which nourished communities along its course. “We see clear evidence of Han Dynasty painting conventions, such as the use of continuous narrative scenes, careful brushwork, and symmetrical layouts,” the American said. “The influence of Han funerary cosmology can be traced in the iconographic choices and compositional structures of early Dunhuang ceiling murals.”

But what truly distinguishes Dunhuang’s murals, Schmid argues, is their spiritual and communal significance. “The murals don’t just depict Buddhas and bodhisattvas in static isolation, they invite the viewer into a cosmic narrative populated by gods, kings, monks, demons, and everyday people.”

A major stop on the ancient Silk Road, Dunhuang never existed in isolation. Early murals reveal Han Dynasty painting conventions, continuous narratives, symmetrical layouts, and precise brushwork, along with traces of Han funerary cosmology. “The murals absorb and reinterpret,” Schmid said. “Chinese technical methods, wall preparation, line drawing, mineral pigments, merge with Central Asian iconography and Buddhist narrative forms. Dunhuang was by far a creative frontier where civilizations met and co-evolved.”

Stone powder pigments made from natural minerals collected from Sanwei Mountain in Dunhuang Photo: Courtesy of Wang Yalin

From pigment to practice

Today, Dunhuang stone powder paintings continue to blend innovation with tradition. As Wang puts it: “Intangible cultural heritage needs to be revitalized, not frozen in time.”

Inside Wang’s studio, she often pauses before her new artwork titled Inheritance. The artwork, painted using the traditional craftsmanship of stone powder painting, shows a student kneeling before a mural, holding a bowl of freshly ground pigments, while a master guides their hand.

“This painting reflects our lineage,” Wang said. “Our inheritance is not only in technique, but in respect for nature and devotion to the art. Every apprentice is part of that chain.”

Wang traces every step meticulously. First, the ground layer, prepared as her ancestors did, fuses pigment with a wall. Then come sketches, enlarged designs, base color application, powder and gold layering, and finally line drawing, which animates each figure. “It is a slow craft,” she said. “Mud and wall fuse. You are working with history, with nature, and with human patience, and time is respected.”

Hou echoed this dedication, noting that the discipline of slow craft is essential not just for preservation but for inspiration. “In an era of rapid change and technological convenience, I insist on hand-grinding minerals, a time-consuming process that preserves the natural luster and integrity of the pigments – qualities lost in machine grinding,” she noted.

As innovation complements tradition, Hou’s studio produces murals on lightweight clay panels for exhibition. The studio has also witnessed how digital tools, online courses, and social media are bringing Dunhuang’s techniques to new audiences. Yet both inheritors emphasize that innovation is an extension, not a replacement, of tradition. “Training the next generation of inheritors requires not only technical teaching but also mentorship in the values of perseverance and respect for tradition,” Hou noted.

In practice, the dedication of today’s artisans ensures continuity. Through social media and online courses, Hou has opened the doors of her studio to thousands of young people across China and beyond. Wang also guides apprentices through desert expeditions to collect pigments, showing them how the same stones were used centuries ago.

After personally “collecting” colors from nature and experiencing the vastness of the Gobi Desert, where the smoke rises straight from the desert and the sun sets round over a long river, students were finally able to quiet their minds and feel the spirit of the Dunhuang murals, Wang said.

She vividly recalled working on the largest piece she had ever created: a ground-based mural inspired by Dunhuang measuring 26.66 square meters. “Dunhuang gets dark very early. I remember laying the artwork on the ground, and the students knelt beside it to copy it. Even after night fell, they didn’t leave, they were completely absorbed in their painting.”

Inside the stillness of the caves, under layers of ochre and azure, the five colors on the painting portray the harmony between earth and imagination, nature and civilization. They speak of a world where faith took form in pigment, and where the river that nurtured China’s heartland also carried its dreams toward distant horizons.

As Wang said as she gently rubbed a handful of ochre between her fingers, “These colors and stories come from the land. But once they touch the wall, they belong to the world.”