In spring 1883, Monet moved the family to Giverny, where Hoschedé-Monet began to paint in earnest. Delighted by her enthusiasm, he began taking her with him on his outdoor painting expeditions. According to the biography of Hoschedé-Monet’s which her brother Jean-Pierre also wrote, “she helped him in all circumstances… transporting his canvases and easel as well as her own. She did it all with the help of a wheelbarrow, following elusive paths, across fields and meadows sometimes drenched in dew. That was the case, for example, with his morning views of the Seine. Here again, she would help her stepfather by taking up the oars of the canoe.”

Monet also suggested exhibitions she might enjoy. In 1891, for instance, he asked his friend Gustave Geffroy, an influential critic, to obtain a pass for her to the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, and later that year, took her with him to dine at the home of the British artist James McNeill Whistler in London (they were visiting her brother Jacques in Lymington) and to see the famous Peacock Room that Whistler created for shipping magnate Frederick Leyland’s mansion near Hyde Park.

How the two Monets compare

Monet’s 1887 painting In the Woods at Giverny: Blanche Hoschedé at Her Easel with Suzanne Hoschedé Reading, confirms that he and Hoschedé set up their easels within spitting distance of each other, or even, if she is the figure in the white dress at an easel in John Singer Sargent’s oil sketch, Monet in his Bateau Atelier (also 1887), squashed together in the floating studio which Monet designed to paint while drifting along the river.

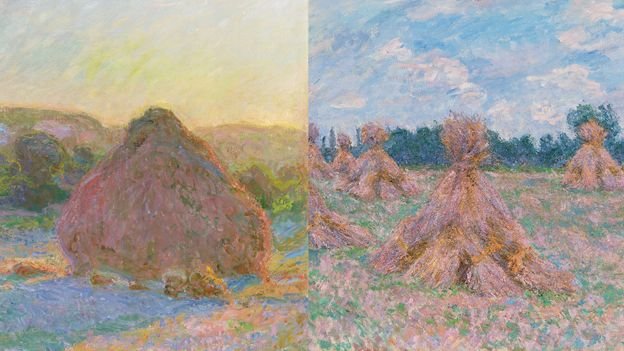

Unsurprisingly, then, Hoschedé-Monet’s paintings often share her mentor’s visual vocabulary: Shadows on the Meadow (Giverny, the Ajoux plain) matches his Spring Landscape at Giverny (1894) for instance, and The Small Grainstacks (Les Moyettes) (c 1894) his Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer) (1890-91). Julie Manet, daughter of the impressionist Berthe Morisot and Manet’s brother Eugène, would also describe two of Blanche’s paintings of “trees reflected in the Epte [that] are very like Monsieur Monet’s painting” while visiting Giverny in 1893.

As Hoschedé-Monet’s great-nephew, the art historian Philippe Piguet, further explains, “her touch is more emphatic, out of concern for capturing what she saw on her canvas rather than what she felt” – meaning that Hoschedé-Monet’s paintings can be described as more solid or direct in their rendering and composition, and less atmospheric, as compared to Monet. She also preferred to paint a subject from varying viewpoints, he adds, rather than, as Monet did, at different times of day.

Consider her painting Haystack at Giverny alongside the Monet Haystacks at Giverny (1893) that was sold at Sotheby’s last year. “They’re at the same or approximate location, but she has distinctly chosen a different view,” says Pierce. “Her painting is also more solid. She has less interest in the quality of atmosphere, and more in really getting down her subject. Her compositions are very well thought out.”