In the 1840 oil painting, a man named Frederick wears a scarlet vest under his black coat and a blue bow tie beneath his translucent lace coll…

In 1848 or thereabouts, a talented artist painted an almost life-size group portrait of the three children of one of the premier slave traders in New Orleans. The painting may have been a memorial to the central figure, 5-year-old William Slacum Lambeth, who died that year.

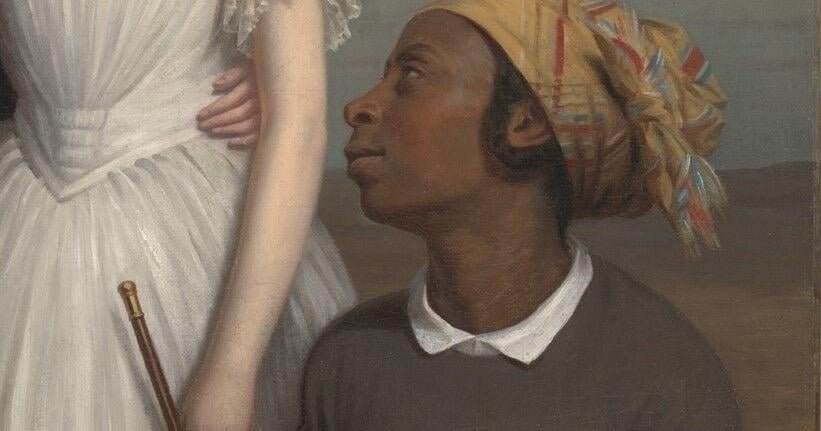

For most of the painting’s history, nobody much cared about the Black woman kneeling in the bottom right corner. Her name and background had been forgotten. She was just the anonymous enslaved servant staring adoringly at young William. In a way, the woman was a prop to illustrate the social order of the era.

But times have changed. Now the enslaved woman is in a position of prominence. The contemporary title of the painting — which was recently acquired by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts — is “Portrait of Leana and the Lambeth Children.” Leana’s identity had been a mystery until it was uncovered — by a Baton Rouge historian, consultant and genealogist.

Baton Rouge historian/consultant/ genealogist Ja’el Gordon discovered the long-forgotten identity of Leana, the enslaved woman in an 1848 New Orleans painting.

Ja’el Gordon is working on two doctoral degrees simultaneously, at two separate universities: higher education at Jackson State University in Mississippi and urban forestry at Southern University in Baton Rouge. Gordon’s research specialty is pre-Civil War Southern history. “I love a great investigative task,” she said. “I love to find things that nobody’s found before.”

That made her the perfect person to look into the enslaved woman’s history. When the owners of the painting offered it for sale, Gordon was hired to provide as much information as possible to help entice possible buyers.

Gordon said she is not at liberty to reveal the painting’s previous owner or who hired her to research the painting.

William Lambeth Sr. was a Virginian who’d made a fortune brokering the sale of enslaved people, Gordon said. He and his family lived part time in a Carondelet Street townhouse in what is now New Orleans’ Central Business District.

Lambeth’s wife died in childbirth in 1845, which apparently prompted him to purchase a 16-year-old Black woman as nanny to his two daughters and son. When his son died, he commissioned a painting by an accomplished New Orleans artist to preserve the boy’s memory. The children’s nanny was included in the composition.

The 1848 painting “Portrait of Leana and the Lambeth Children,” memorialized the five-year-old boy in the center, but also symbolized the social hierarchy in the time of slavery.

Her servility is clear. She is literally positioned at the exact same level as the family dog. She and the dog gaze at William, while the two other Lambeth children, the sisters Fanny and Dora stare somberly out of the canvas.

Gordon said the young woman’s presence in the painting demonstrates the master’s wealth and paternalism. Her posture suggests that she is genuinely devoted to the children, whether or not that was true.

Gordon said that no one associated with the Lambeths in the historical record seemed to match the anonymous young woman in the painting. But in a much-deteriorated notary record in the New Orleans Clerk of Court office, she hit pay dirt. Lambeth paid $650 for an enslaved teen named Leana not long after his wife died — $25,000 in today’s economy, Gordon said.

Gordon learned that Leana came from Chickasaw County, Mississippi, and she set out to find any records of her there. Unfortunately, Gordon said, the county’s early 19th-century records had been burned by Union troops during the Civil War. But the local genealogical society had some historic archives. There, Gordon discovered that Leana had been sold by a woman named Jane O’Neil who was in the midst of a divorce.

The painting, which was meant to immortalize a dead child, now assumed a new role. The painting gives an identity to a woman who lived at a time when people like her “were stripped of their identities,” Gordon said. In a way, she said, “it gives her an opportunity to speak.”

Leana has been “solidified in history,” Gordon said. The painting is no longer “just showing the family of a slave owner.” It is, in a way, a triumph.

Gordon said Mr. Lambeth died in 1853, and his daughters were sent from New Orleans to live elsewhere. She’s unable to say where the painting ended up after that.

The “Portrait of Leana and the Lambeth Children,” was painted in New Orleans in 1848, presumably to memorialize the death of the young boy in the center. Recent research has revealed the identity of the enslaved teen to the right

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts acquired the 180-year-old group portrait in 2024. Leo Mazow, the museum’s curator of American art said the oil-on-canvas is roughly 5 feet wide and 6 feet tall, and remarkably well preserved, considering its age. Mazow declined to reveal what the museum paid for the painting.

The artist who produced the large, expensive family keepsake is unknown. The museum is currently comparing the style of the unsigned painting to works of a handful of New Orleans artists from the period in hopes of assigning an attribution.

And there are other mysteries that may never be resolved. For instance, he said, it’s unclear if the subject of the painting, young William, had already died when the painting was commissioned, or had fallen ill — in any case, the funeral for the young boy was held at the family’s Carondelet Street home.

One thing’s for certain. Then and now, Leana’s place in the group portrait is crucial.

Leana’s face and the yellow tignon that wraps her head are “the most crisply painted” details of the group portrait, Mazow said. Her gaze, he said, compels viewers to enter the scene.

The painting, he said, is bound to produce conflicting reactions. “It’s a viscerally beautiful painting,” and it “reasserts the personhood” of Leana, but it also indicates the profound injustices of slavery. The “congruence” of Leana and the family dog, he said, is “disturbing.”

Mazow gives “all the credit” to Gordon for researching the piece. “She went above and beyond,” he said.

Paintings of enslaved people are rare, and paintings of identifiable enslaved people even more so. As time goes by, Mazow said, “It’s our hope to tell more of her story and people like her.”

“I hope that people recognize the complicated nature of family and race relations in the American South,” Mazow said.

Gordon said she’ll continue her research on the mysterious Leana. “We don’t know who her parents were, we don’t if she had any children, we don’t know if she was childless. So far she is just solo.” Leana, Gordon said, deserves to have descendants.

What’s wrong with this picture? In an 1837 painting, a Black teenager stands beside a trio of White children. A recent historical discovery te…

The trouble with this story is you can’t really be sure of anything. A famous 19th-century artist was long thought to be a free Black man, con…

This is the long, complicated follow-up story to an earlier complicated story about a beautifully preserved, circa 1845, pastel drawing of two…