rintmaker Saad Ahmad recently showcased his work at the White Wall art gallery in Gulberg, Lahore. Titled Witness, the exhibition was proof of Ahmad’s curious capturing of nature’s resilience and its translation through the laborious layers of printmaking, which seemed to redefine the ordinary and mundane as sublime.

Memorabilia, such as the gentle patter of rain on car windows and the soft contours of clouds, was vividly depicted as a form of travelogue. These cherished elements not only inhabit our personal experiences but also resonate in our collective memory, forming a tapestry of shared nostalgia. Ahmad transferred these experiences onto a plate and encapsulated emotions and narratives that might otherwise fade with time.

Even further, as the process claims, when this visual representation is transposed onto paper, it creates a profound echo, a reflection of not only the original experience but also the myriad of emotions and recollections that it invokes in us.

The process of ‘witnessing’ was manifested through an array of mark-making techniques across a variety of surfaces, each reflecting the artist’s perspective.

The exhibition invited the audience to delve into the intricate interconnectedness of human consciousness, highlighting our collective experiences that shape our world and its comprehension. The viewers shared this act of ‘witnessing’ along with the artist, to foster a sense of unity and harmony in an interdependent bond with Nature.

Memorabilia, such as the gentle patter of rain on car windows and the soft contours of clouds, is vividly depicted as a form of travelogue.

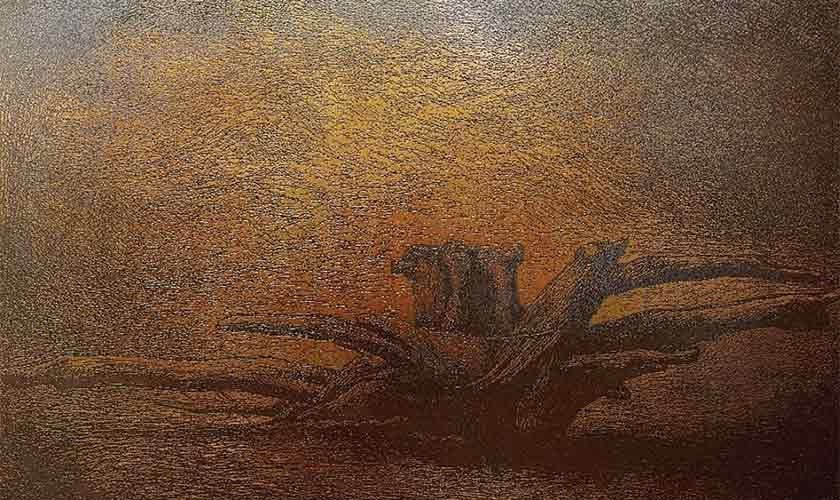

The same image is displayed in Comfort of Knowing and A Sate of Becoming, each time featuring a distinct iteration that underscores the versatility and liberty of the medium. In this stage of production, there is a deliberate shift towards exploring the possibilities of presentation that allows the viewer to see fraternal images from the same womb, emphasising the nuances, sometimes in colour, its absence or in its rotation.

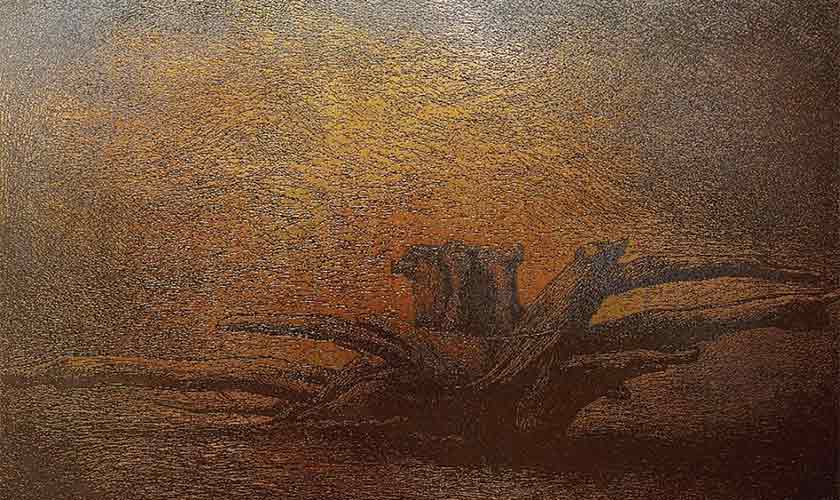

Semi-representational images contain memory of an organic form, etched with a sense of intrigue and formulate a conspiracy regarding not only their origin but what they have become. Headless figures or a barren tree, frozen in time like fossils, take hundreds of seconds in the act of unbecoming.

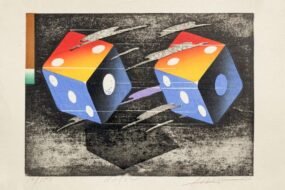

The striking red square image, in particular, invites a multitude of interpretations, each resting in the viewer’s perception. However, its capacity to be tied to a specific source is somewhat constrained; it remains an abstraction rooted in the artist’s imagination. Despite this, a universal resonance allows individuals to forge personal connections with the work. In much of Ahmad’s work, a deliberate lack of glass installed within the frames is a ploy for the viewer to become one with what is present. Ahmad employs multiple techniques and surfaces for the transfers, each material bringing its unique history and identity to start a discourse with the image. A stainless steel plate, etched and inked, hung on the wall, defies its lack of completion. It raises questions of aesthetics in creative practices and the idea of perfection, whether it is the act of universal resolution to a concrete objective or the creator’s decision of knowing the point of conclusion.

The image transfer on a bone plaster tray features a smooth surface, showcasing the diversity of ink as a medium and its interplay with the fragility of plaster. Whereas, linen cloth print serves as a substrate, offering a rich canvas that complements the depth of the carved wood.

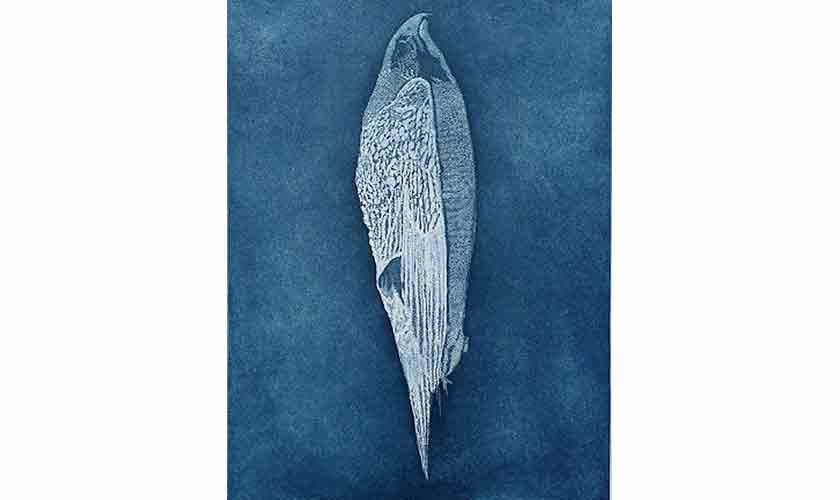

The two blue prints serve as a metaphor for nature, capturing its essence and the underlying process of decay in concept as well as in form. The jasmine offers a dual perspective on the natural world, illustrating the delicacy between creation and decay. As plants draw essential nutrients from the organic matter around them, they thrive on the remnants of life that once flourished.

Printmaking is an art form that embodies this cycle of erosion; it transforms materials through the decay of surfaces. The acid stings the metal plate, effectively stripping away electrons that are fundamental to the existence of matter and render the surface naked. This chemical reaction leads to the dissolution of the metal, while converting the metal into salt as sediment to reside in the liquid and weaken it.

Within the context of the image of the bird in blue, this transformation could be represented as the ocean or the sky as the two sides of the same coin, symbolising the uniformity between life and death in nature. Through these layers of meaning, the work invites viewers to reflect on the interconnectedness of all things living, and emerge in the umbrella of this cycle.

Sousan Qadeer is an interdisciplinary artist and educator based in Lahore