James G. Todd Jr., a Missoula artist known for his portraits and prints of authors and musicians as well as fiery commentary on social subjects, all done with intricate detail, died the last weekend of April. He was 87 years old.

He took his own iconoclastic path to becoming one of the state’s most respected artists. He grew up in a working class Great Falls family who encouraged his drawing from an early age. He learned age-old printmaking techniques in art school and in the mid-1960s applied them to contemporary subject matter, like images of jazz musicians and pointed anti-war prints during Vietnam.

While he was steeped in the history of the state, he was more liable to portray difficult periods in its past, or its famous authors, than to delve into landscape work. Somewhat unusually, he taught both studio art and humanities at the University of Montana for decades.

People are also reading…

James Todd, a widely recognized printmaker and artist, is seen in 2002 at the Missoula Art Museum during a retrospective.

He once said that art is “a depiction of the mindset of the people, it’s like a prophecy.” He added that an artist has to decide what they want to portray. In his case, he didn’t care if a viewer found something in his work morbid or ominous. His concerns were social concerns, things that affect everyone.

“To me, truth is very important. It is important to me to know what the hell is going on. I need it for my art and I need it for me,” he said.

He taught at UM from 1970 to 2000, including stints as humanities program director and chair of the art department. One of his courses was on the social history of art. He was a “real scholar,” according to Stephen Glueckert, the retired curator at the Missoula Art Museum.

“In some ways he saw no boundaries between scholarship, and the practice of art, perhaps more like, art and music were avenues of truth-telling and authenticity. If you have something to say, you could and should be well informed and sharpen your language,” Glueckert wrote in an email.

“He was not much for ‘art for art’s sake.’ I like to think of him as what some art historians call an ‘instrumentalist,’ meaning he saw art and music as instruments of expressing specific messages.”

A self-portrait by James Todd.

Early life

Todd was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on Oct. 12, 1937. During World War II, his family moved to Seattle, where they lived in a low-income housing project. His father, James Todd Sr., was a steel mill worker and later a businessman who also boxed, and his mother, Doris, worked in department stores.

Todd began drawing when he was a toddler. His parents encouraged him, as well as his three brothers, to pursue art.

“My parents’ attitudes were very important. My parents were working class people, but there was art in the atmosphere. We weren’t raised with Mozart, but my parents were very receptive to art and very promotional of it,” he said in a 1980 interview.

“Art and creativity were not only tolerated by my parents, but we were made to feel very self-confident; we were told, ‘This is OK. This is an ability that others don’t have.’ ”

In 1948, the family moved to Great Falls. His earliest art education came through private lessons with a Catholic nun. When he was young, the city had a jazz venue, the Ozark Club, where he and his friends would sneak in to listen to music, cementing a lifelong love of the genre. He began to play drums himself and draw jazz musicians when he was in high school, a practice that continued throughout his career.

Glueckert, who also grew up in Great Falls, said the downtown was “a stimulating and lively place,” with music clubs, a large bookstore, multiple movie theaters, and even two newspapers.

“Jim’s insatiable curiosity led him on a path away from Great Falls, where he stuck by his convictions, traveled, taught, and became a very respected artist and disciplined scholar,” Glueckert wrote in an email.

Todd became an avid pool player at the local spot, Hussman’s, and learned the more obscure game of snooker. The hall and the game itself were subjects in prints he made.

James Todd, “Charles Mingus” (woodcut print on paper, 8 by 7 inches.)

He began studying at the College of Great Falls before transferring to the Chicago Art Institute in 1959, where he learned under Adrian Troy, a widely recognized printmaker, and began exploring wood engravings — a form of printmaking where the artist carves on the denser end-grain of a wood block rather than the plank. He also studied at the University of Chicago.

He served in the Army in Germany, where he met his wife, Julia, and they returned there for three years where he taught and worked in an older country with a still active culture of wood prints.

Printmaker Bev Beck Glueckert, who studied under Todd, said he was influenced by German Expressionist printmakers.

“Jim was attracted to the immediacy and directness of the process, as well as the ability to use powerful bold strokes to produce striking black and white multiples,” she wrote in an email.

Regarding engravings, she said the medium likely drew him because of his interest in portraiture and detail.

“He was able to achieve the desired emotions and power of personalities utilizing the intricate and varied types of mark-making and textures that are possible with a burin and harder wood. And he became a master of the technique.”

It was during his time in Germany that teaching emerged as a path to financial stability and artistic leeway.

“I had three one-person shows of my prints and paintings, and decided then that I wanted unhampered freedom in my art, and did not want to be a business artist. To support my family my decision meant I would, if possible, continue teaching,” he said in the catalog for a 2017 exhibition.

After bouncing around between campuses, he earned a B.A. from the College of Great Falls, a Master of Art and an MFA from UM, and was offered a teaching position in 1970. He stayed in Missoula for the rest of his life, where he and Julia raised their children.

“Montana Portraits, Chief Charlot” (print from wood engraving, 3 by 4 inches)

A scholar and an artist

The style in his portraits was reverent and carefully composed to give insights into his subject. Bassist and composer Charles Mingus, whose music spanned the human experience from joy to turmoil and rage, gazes downward in thought. Author James Welch, a colleague at UM, has a sly grin.

In a 2002 interview about a retrospective at the Missoula Art Museum, he said his portraits of musicians were deliberately serious in a contrast to the pop culture imagery.

“They traditionally are portrayed as revelers or entertainers, which tends to undercut the seriousness of what they do,” he said.

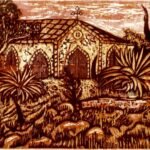

In 1976, Todd produced a history of labor in the state called “Montana: A Buried History.” Commissioned by the Executive Council of the Montana Federation of Teachers for the U.S. Bicentennial, he aimed to fit 200 years onto a 4 by 8 foot panel. It’s now held in the collection of the Montana Historical Society. He told the Missoulian during a tour of high schools that “the labor history of the state is buried, buried, buried.”

The sprawling painting covers white settlement, the decimation of Native American tribes, the hanging of labor organizer Frank Little in 1917, the expansion of the railroads, a mine shaft dug deep into the earth, and much more.

“I do not pretend to give a complete or detached overview,” he said. “Rather, I attempt to symbolize events and connections in the history of the state which I believe are frequently ignored and sometimes even repressed.”

He worked in series throughout his life, including ones on the seven deadly sins, Montana authors, famous printmakers, the writer Franz Kafka’s novel, “The Trial,” and more. His portrait of the poet Pablo Neruda was printed in a collection, “Still Another Day.”

Lisa Simon, the co-owner of Radius Gallery said Todd was an avid reader, the type who would work his way through the Encyclopedia Britannica.

“He uses art to think,” she said.

For instance, one of his drawings in pen on paper, “Indian Killers,” began with a photograph he saw in a magazine of an Indigenous girl surrounded by white men in military garb.

He drew her, and then “starts free associating all the creativity of Indian cultures,” Simon said. Those fill in the sides of the image, with homages to their artistic styles. Finally at the bottom, he weighs in with images of “white generals who thought of themselves as Indian killers.” They’re listed in the subtitle: “C. Columbus, F. Pizarro, H. Cortez, K. Carson, A. Jackson, G. Custer, J. Chivington, G. Sherman, J. Cavanaugh.”

That’s just an example of how injustices would feed into his work.

“Valuing art was part of how you get to valuing human life equally so the hierarchies of race and gender would fall away,” she said.

Todd revisited childhood drawings for an exhibition and catalog, “Looney Toones.” He drew the originals when he was between 5 and 8 years old. He thinks the scenario for “Knight Nurse,” was sparked by a kid’s confusion of the works “knight” and “night.”

In Missoula, Todd has shown at Radius for years, although at first he was reluctant because he didn’t think his work was made for galleries. In a tribute post, Radius cited his mentorship of younger teachers and artists.

One of those students was Missoula printmaker David Miles Lusk, who took lessons from him during his senior year of high school.

Todd’s serious approach to technique, versatility and dedication to producing art with something to say had a “massive influence” on his work.

“He laid this foundation that has been so crucial in my career,” Lusk said.

Todd’s last museum exhibition in the city was “Looney Toones,” which opened at the Montana Museum of Art and Culture in 2017 and toured the state.

The unusual project began after his retirement from UM, when his mother gave him drawings he’d made as a child during World War II. Fascinated by the imagery, which required his own process of decoding the scenarios he’d drawn, he made a series of color prints and exhibited them all side by side.

In the catalog, he discusses how much he was inspired by comic books as a kid and explores both the exuberance and the anxieties he saw in the sketches.

The original drawing of “Knight Nurse,” made when Todd was a child. He stayed true to his compositions, including the orientation. With the woodblock printing process, the final piece is reversed.

A printmaker’s hand

Jim Bailey, a UM printmaking professor and director of its in-house press, Matrix, overlapped with Todd as a faculty member. They collaborated on several projects together after Todd retired: One was a series, “Seven Deadly Sins,” and another was a portrait of Chief Joseph. In the “Sins” series, Todd tackled a subject that printmakers have mined for centuries, but with his own twist, Bailey said. There are references to current events, such as Guantanamo Bay, corporate greed and reality TV.

Bailey said Todd had a traditionalist’s technique and primarily worked in black and white. If he did use color, he applied it by hand afterward. Todd has attributed his use of color to a trip to Mexico, where he saw social realist artists and a way to employ hues without blending.

James Todd, “Jacobean: Owl Man” (relief monoprint on paper, 12.5 by 14.5 inches)

He used traditional relief printing tools along with engraving ones. For the most part, he never used a mechanical press. He burnished his prints manually — applying ink to the block and then pressing it on paper by hand.

“Unlike a lot of printers, who might run a full edition, he would print as he needed,” he said.

“He had a really strong hand, which I remember one time when I made a good pool shot, he slapped me on my back. I thought I was going to cough out a lung,” he said.

Todd worked in both wood engravings and woodcuts. Traditional engravings are done on the end grain of a block of wood, which is much harder material and allows for great detail. Woodcuts are carved on the plank side of the wood, which is softer and calls for tools like gouges.

Much of his work was made with a mix of engraving tools and gouges, Bailey said. He often used a multiple line tool, which allows an artist to make sets of parallel lines of the kind you see on dollar bills.

His technique earned him membership in international groups like the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers and the Wood Engravers Network. Both are prestigious outfits, Bailey said, that require the submission of a portfolio of prints that’s reviewed by a committee. Being a member raised his profile considerably.

“It was through those organizations that he got his work out there internationally,” he said. “Both of those societies will organize group exhibitions that would travel around the world, oftentimes.”

His work is held in collections in China, Germany, England and Mexico, as well as museums in his adopted home state.

The Montana Museum of Art and Culture had already been working on a retrospective with Todd that will open next year. The museum is working on plans to host a memorial in early summer.

Todd was producing new series and drawings right up until the end of his life, Bailey said, and his opinions had stayed sharp as his tools, tackling subjects like the pandemic.

“He was always staying up to date on what the current issues were — and really calling people out visually,” he said.

In a 2002 interview, Todd described the cyclical nature of drawing.

“It’s like we’re solving a problem of some kind,” he said. “We do temporarily have the satisfaction of solving it, but in the end it isn’t as good as it could have been, so it starts again.”

James Todd, “Montana Portraits, Norman Maclean,” print from wood engraving, 3-by-4 inches.

Cory Walsh is the arts and entertainment reporter for the Missoulian.