Mediums have often defined artists’ careers, but rarely has an artist defined the history of a medium the way Devraj Dakoji has contributed to the progression of printmaking. His engagement with the medium, spanning a career over five decades, is the subject of a recently-concluded exhibition, titled Signed, Lower Right at Delhi’s Gallery Exhibit 320, with over 60 works on display. Interestingly, printmaking wasn’t Dakoji’s first calling as an artist. Trained in painting at College of Fine Arts and Architecture in his hometown in Hyderabad, he worked with watercolours and tempera, until a chance encounter with an exhibition of prints on World War II by German artist Käthe Kollwitz left him spellbound. “She did a lot of interesting work with prints, using woodcut and lithographs, which captured the suffering of the people during the war evocatively. I was moved by the depiction of the tragedy. That inspired my interest in printmaking,” says Dakoji, 76, adding that when he tried to enquire about opportunities to explore printmaking, there were none in Hyderabad.

He then enrolled in MS University, Baroda, where under the tutelage of masters such as Jyoti Bhatt, N.B. Joglekar, and K.G. Subramanyan, he embarked on his journey as a printmaker. Signed, Lower Right assumes significance in the way it documents Dakoji’s rendezvous with the medium; his fascination, learnings, and experimentation, both as a student and, later, as a mentor. His early works, particularly his Organic series, created in the 1960s and 1970s, defy the monochromatic imagery convention ally associated with the medium. The works have bright hues of blues and reds that render the colour lithographs and etchings the quality of a painting, display ing the versatility of a medium that has its origins in industrial reproduction.

Dakoji elaborates that this was the period where he was oscillating between his then primary identity as a painter, and his nascent yet evolving sensibilities as a printmaker. “Few people have experimented with colours in printmaking. I started my career with painting landscapes, so when I began working as a printmaker, I transferred those landscapes into prints. I continued working in colour even after going to London at the Chelsea School of Art. But, eventually colour seemed to feel like a painterly form of expression,” says Dakoji, who created his famous monochromatic Rock series (1976) in London.

Also read: Aamir Aziz, Anita Dube and the hypocrisy of political art

View Full Image

The deeper Dakoji dived into the world of printmaking, the curiouser he got. Following his stint as the chief supervisor of graphic studios at the department of art, Garhi at Delhi’s Lalit Kala Akademi (1977), he realised the sheer dearth of awareness, and opportunities, in the field in the country. “When I joined as the supervisor in Garhi, I realised that most of the artists had very little experience with the medium. My job was to guide them not just on how to use the medium, because, you see, you use lithograph differently, and intaglio differently and woodcut is used differently; but it was also about guiding them on using the medium correctly to express their ideas. Because only if I guided them properly could they find their unique expression,” says Dakoji.

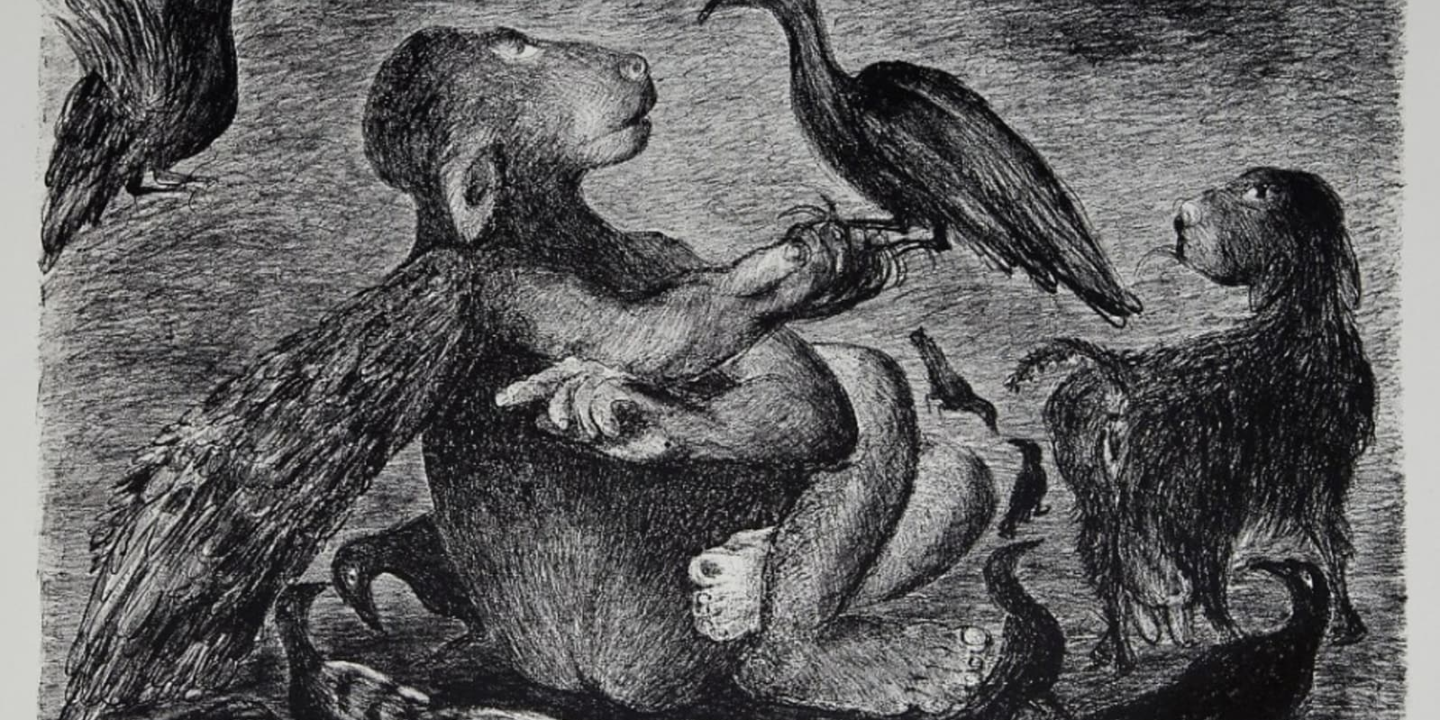

In 1985, while attending an artists’ workshop in San Diego, he heard a peacock’s call at dawn, a sound that was commonplace in Garhi. The universality of the bird turned into a moment of epiphany for Dakoji, and pranamu (Telugu for life force) became central to his practice as he turned to forms of nature for inspiration, with the peacock becoming a recurring motif. The innocence of his philosophical understanding was complemented by his artistic maturity, which now had a new found appreciation for the monochromatic renditions of printmaking. The Pranamu series, exhibited in Signed, Lower Right, saw him revisiting animal forms—elephants, monkeys, crows, among others—through the years; the latest one being as recent as 2022.

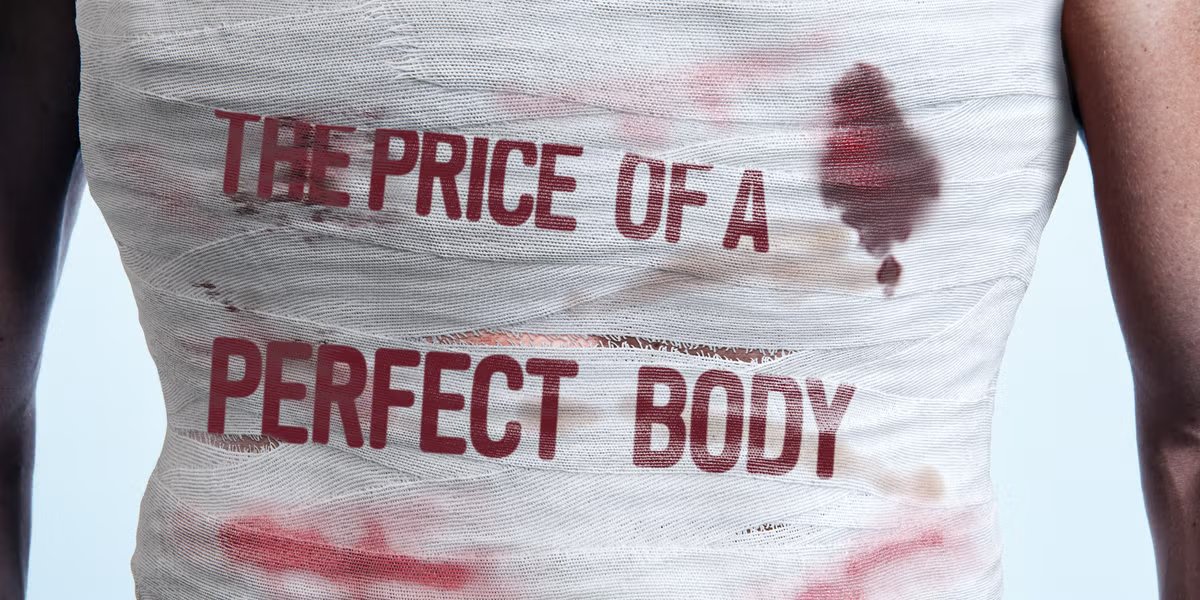

Dakoji’s quest for knowledge, however, had only begun. Less than a decade later, he was at the Tamarind Institute in New Mexico where he underwent a year-long training in lithography. Here, he was introduced to chine-colle, a printmaking technique that uses two papers of differ ent density to print images. “Chine-colle was first introduced by the Chinese to make children’s books captivating. They came up with the technique to make colourful images for children’s books, which until then were black and white and boring,” he says, adding, “Printmaking, like painting, or any other medium of art, is a way of self expression. But printmaking allows collaborations with other artists, furthering an exchange of knowledge and keeping the cycle of learning going.”

Also read: Viewing a rare Caravaggio up close

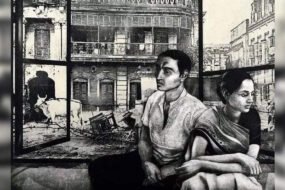

In one such exchange, he collaborated with modernist M.F. Husain in 2000 to create two untitled works (lithograph and chine colle). “Husain always liked colour. When we worked together, he inspired me as much as I him,” says Dakoji. On his return to India from New Mexico, Dakoji established Atelier 2221 in Delhi, along with wife and fellow artist Pratibha, to increase awareness about printmaking among young practitioners. Dakoji’s relationship with printmaking, has come full circle, much like the theme of his Wheel of Life series, which celebrates the cyclical nature of life. Today, he continues to share the knowledge he has accumulated through the years, now as a master printmaker at the Robert Black burn Printmaking Workshop in New York. At 76, Dakoji is as fascinated with printmaking as he was when he first laid eyes on Käthe Kollowitz’s war prints.

Trisha Mukherjee is a Delhi-based writer and arts professional.