In the United States, cursive is dying a slow, loopy death. Roughly only half of the states require kids to learn it, leaving a generation of children to try and decipher grandma’s birthday cards like they’re written in ancient runes.

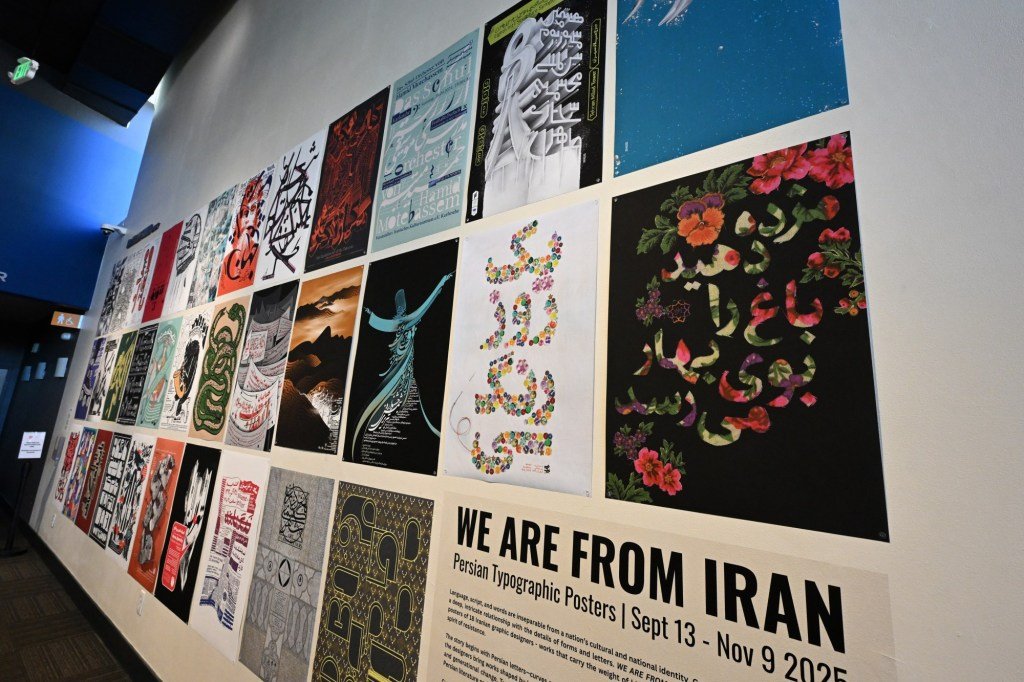

Entering the exhibit “We Are From Iran”, a display of Persian poster art at the Dairy Arts Center, 2590 Walnut St., Boulder, feels a bit like being reintroduced to what letters are capable of. In Farsi, words curve right to left, looping around the gallery walls like poetry going for a meandering jaunt.

Curated by Parisa Tashakori, the exhibit showcases the work of 18 Iranian graphic designers who use typography not just to decorate a piece of paper, but to speak — loudly.

Tashakori, a designer, artist and professor at the University of Colorado, was contacted by the Dairy Arts Center about a year and a half ago to exhibit her poster designs. She instead saw an opportunity to do something bigger — something that would reach across countries, languages and generations.

“I decided to invite other Iranian designers to show their work, too,” Tashakori said. “We have such a dynamic design community, and I wanted to reengage with them and bring that culture to Boulder.”

Before moving to the United States in 2017, Tashakori had already built a long career as a designer and curator, collaborating with international agencies and cultural institutions to explore how graphic design can shape social dialogue. She saw the Dairy exhibition as a chance to bridge cultures, knowing that Iranian typography had rarely been shown, or even explained, in Colorado.

“In Iran, we write from right to left, but our numbers go left to right,” she said. “That difference creates a kind of rhythm and complexity. I wanted audiences here to experience that.”

Persian typography, she explained, is inseparable from poetry. The visual traditions behind Iranian script reach back more than a thousand years, to poets like Ferdowsi , who chronicled Iran’s mythic past in his epic poem “The Shahnameh” (“The Book of Kings”), along with poet Hafez, whose lyrical verses on love and faith are still recited in Iranian homes today. For centuries, poetry and calligraphy evolved together, in a union of language and line that shaped how Iranians learned to see.

“We have so many different kinds of calligraphy in our culture,” said Tashakori. “In our tradition, we care about beauty and decoration. Even the smallest detail matters: from the shape, the line, to the space between.”

For this exhibition, she focused on designers who explore typography as a form of feeling, rather than just function. In the Dairy’s gallery space, posters hang in neat rows, featuring colors almost too alive for the white walls behind them. Electric blues and yellows clash with smoky grays; black calligraphy curls into bright blocks of neon green.

Some works are layered with both Farsi and English, their messages flipping between worlds. One reads “NO WAR” in cobalt blue across a yellow background. Another, stark and haunting, shows a white dove with a plume of fire rising from its head. Everywhere, the text feels alive, and letters loop and braid together like filigree.

The show gathers artists from across generations and continents. Some still live in Iran, working within tight creative boundaries, while others now live abroad, teaching, designing, or navigating the dual identities of being an exile and an expat looking for belonging.

“There are two generations in this exhibition,” Tashakori said. “Millennials and some Gen Z: Those who learned design by hand, and those who grew up fully digital. Both carry the same soul.”

One of those artists is Siamak Pourjabbar, an illustrator and designer now based in Canada, whose pieces sit somewhere between surrealism and social commentary.

“My main focus has always been illustration,” he said, via email. “I design my posters based on an illustrated concept first, then integrate typography into the composition. I treat letters as visual elements, as part of the drawing itself.”

Four of his pieces appear in the show, each one layered with personal mythology. One reimagines “Beauty and the Beast” through Persian calligraphy. Another imagines a concert by Pearl Jam in his hometown of Rasht, Iran. It’s a show that exists only on paper, but still feels real.

“In the film where the poster appears, I imagined that Pearl Jam was performing in my city, on my birthday,” he wrote. “It connects my life to the band and my city to my dreams.”

For Pourjabbar, design isn’t about translation so much as feeling.

“I believe in the power of design to tell stories that don’t need translation,” he said. “My goal is to reach that emotional point where the audience can feel something, even if they can’t read the text.”

In Tehran, Majid Kashani works under different circumstances. Sending files across borders is complicated, and so is creating art in a country where political scrutiny is routine. Yet his work, which is lush with looping Persian letters that seem to spin on their own axis, feels unrestrained.

In one of the show’s most arresting pieces, a green serpent coils across the page, its body made of looping Farsi script. The letters glisten like scales, winding and twisting around one another until it’s hard to tell where language ends and anatomy begins. This is Kashani’s “The Voice of One Hand,” a theater poster that turns typography into a living, breathing creature.

“It’s part of our culture to find ways to speak even when we can’t,” Kashani said. “When we face red lines and restrictions in artistic expression, we create our own visual language to cross the boundaries of censorship.”

That kind of coded communication runs through much of Iran’s graphic design, where shapes and flourishes are messages disguised as beauty.

“This language is clear to Iranian audiences, but it may seem complex to others,” he said. “Still, Iranian designers have become very successful internationally. I dare say Iranian graphics have become an independent and important style in the world.”

Kashani’s posters often blend tradition with modern urgency.

“Because of Iran’s long history in Persian script and traditional calligraphy,” he said, “we have access to vast and valuable historical resources that we can modernize and use in our graphic design.”

His letters trace lineage, resistance and the evolution of how Iranians have learned to express themselves when speech isn’t always free.

“While politicians use the language of war and threats,” he said, “this exhibition creates human and cultural relationships between artists and the people of Iran and the United States.”

Tashakori has a poster in the show, too. Her piece depicts Boulder’s Flatirons, the sandstone slabs that rise above the city like an open book. But instead of stone, the ridges are made of text in a topography of language.

“I wanted to show my second home,” she said. “I came here seven years ago, and Boulder has become a part of my story.”

Tashakori teaches in CU Boulder’s design program, where her students are learning to work alongside the thing that worries many artists most: artificial intelligence. The exhibit’s final wall poses the question in English and Farsi: Can a machine feel typography?

“In Iran, many people are experimenting with AI, but it’s not like here,” she said. “It’s more limited and also more controlled. There are restrictions.”

For her, the problem isn’t whether AI can make a typeface that looks human, but whether it can understand why a human would draw one in the first place.

“Typography carries emotion,” she said. “It carries memory. A computer can repeat a shape, but it doesn’t know what it means to lose your language or to fight for your freedom with words.”

She added: “Design is part of identity. If we lose that, we lose ourselves.”

“We Are From Iran” opened on Sept. 13 and runs through Nov. 11 at the Dairy Arts Center. Admission is free, and the gallery is open daily.

An artist talk with Tashakori will take place at 5 p.m. on Oct. 28 at the Dairy, giving audiences a chance to hear more about the ideas behind the work and the stories of the artists who created it.

Featured artists include Mohammadreza Abdolali, Mojtaba Adibi, Sina Afshar, Hoda Akhlaghi, Reza Babajani, Mahdi Fatehi, Nahid Ghahremani, Amirhossein Ghoochibeik, Hamed Hakimi, Masood Jazani, Majid Kashani, Amir Karimian, Mina Nasliyani, Maryam Naderi, Siamak Pourjabbar, Mehdi Saeedi, Reyhane Sheikhbahaie and Parisa Tashakori.

For visitors accustomed to typing on keyboards or allowing predictive text to finish their sentences, beware: The sight of handwriting this alive is startling.