A century ago, French writer André Breton published a manifesto that would go on to become one of the most influential artistic texts of the 20th century. Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism launched a movement that transformed not only visual art, but also literature, theatre and film.

Surrealism drew on developments in psychology to herald a revolutionary new way of doing, seeing and being. It is, as art critic Jonathan Jones once noted, “the only modern movement that changed the way we talk and think about life”.

Surrealism also fundamentally changed the way we make art. Its cultural impact and legacy can be felt in, to pluck three random examples, the cinematic dreamscapes of David Lynch, the lyrical cut-ups of Bob Dylan and the monumental sculptures of Louise Bourgeois.

The term itself has entered our everyday lexicon. By the same token, some question its significance and aesthetic merits. Moreover, to borrow a couple of rhetorical questions posed by Mark Polizzotti in a book marking the movement’s centenary: “Does Surrealism still matter? Has it ever mattered?”

These questions are hardly new. They’ve been around since the movement’s inception – and continue to be asked in our historical moment of catastrophe. As Polizzotti writes:

young people of the 21st century could hardly be faulted for wondering what a bunch of eccentric writers and artists showing off their dream states could have to do with such pressing concerns as social and racial injustice, a faltering job market, gross economic inequities, the decimation of our civil liberties, questions of gender identity and equality, environmental devastation, education reform, or, once again […] the spectre of world war.

The answer, Polizzotti points out, is simple: “Surrealism engaged with all of these crises.”

EPA/Tytus Zmijewski

While Surrealism started as a literary movement, it quickly evolved into a formidable platform for critiquing dominant sociopolitical inequalities and systems of oppression.

In both word and deed, the surrealists opposed warmongering and colonial expansion. They railed against religious dogma and championed the freedom of sexual expression.

Breton perhaps put it best in 1935. “From where we stand,” he said, while tipping his hat to Karl Marx, “we maintain that the activity of interpreting the world must continue to be linked with the activity of changing the world.”

WWI and meeting Jacques Vaché

Born in Normandy in 1896, André Breton was the only child of a policeman and a seamstress.

While studying medicine, Breton developed an interest in mental illness. He also had a passion for poetry. At an early age, he started exchanging letters with the prominent avant-gardist Guillaume Apollinaire, who coined the term “surrealism” in 1917.

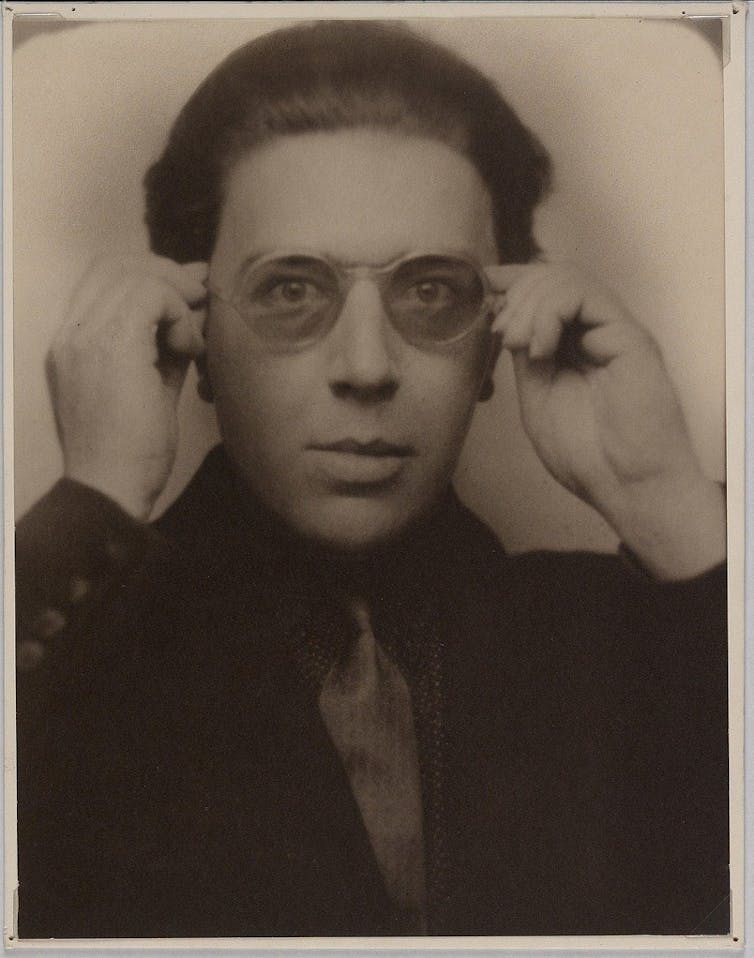

Wikimedia

Breton’s interests were disrupted when he was conscripted into the French army in 1914. During World War I, he served as a stretcher bearer, dealing firsthand with shellshocked soldiers. He also worked as a nurse in Nantes, France, where he met a wounded Jacques Vaché.

According to art historian Susan Laxton, the dandyish Vaché was in equal measure “disdainful and deeply cynical”, seeming to live “in a perpetual state of insubordination”. His unconventional approach to life and creativity had a profound impact on Breton’s thinking about Surrealism.

Vaché had little patience for most writers and artists. He was, however, a big fan of Alfred Jarry – best known for his scandalous drama Ubu Roi (1896). Jarry is frequently cited as an influence on Dadaism, an anarchic art movement that was developed in Europe in 1915 and led by Tristan Tzara.

The Dadaists thumbed their noses at convention and embraced chaos, irrationality and spontaneity. As Tzara explained, Dadaism was vehemently opposed to “greasy objectivity, and harmony, the science that finds everything in order”.

Breton was impressed. Keen to establish his credentials as an artist, he set out to build his own avant-garde coalition.

The rise of automatism

Enlisting Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault, Breton set up Littérature. Running from 1919 to 1924, this review published many key surrealist works, including excerpts of Breton and Soupault’s book The Magnetic Fields (1920).

Drawing on Sigmund Freud’s concept of the unconscious, this groundbreaking collaboration marked the first sustained use of a practice called surrealist automatism.

The Magnetic Fields was written in secret over the course of a single spring week in 1919. The guidelines Breton and Soupault established for themselves were simple. They would engage in writing sessions that could last for several hours at a time – often inducing a state of shared euphoria – without any chance for reflection or correction.

The aim was to bypass rational modes of thinking and tap directly into the imagination, thereby producing a revolutionary new kind of poetry. In the words of art historian David Hopkins, this practice “was predicated on the conviction that the speed of writing is equivalent to the speed of thought”.

Following this breakthrough, Breton and the surrealists continued to refine the technique, pushing it further into new, untrammelled realms of creative possibility. With the subsequent publication of the Manifesto of Surrealism, Breton solidified the movement’s core principles. In it, he offers a definition:

Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dreams, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principle problems of life.

In other words, Surrealism was not just an artistic endeavour, but a philosophical stance that sought to radically rethink experience and existence.

Elsewhere in the manifesto, Breton introduces the key surrealist concept of “the marvellous”. For the surrealists, the marvellous could be found in poems, paintings, photographs and everyday objects. It was experienced as a shock or jolt, a moment of recognition that allowed one to transcend the ordinary and glimpse the sublime hidden within the apparently mundane.

By rejecting traditional modes of understanding and embracing the unconscious, the surrealists attempted to upend the established order of things. They viewed automatism and the marvellous as ways to access deeper truths, free from the constraints of rationality which they believed had long dominated Western thought.

A movement transcending borders

The events that followed the publication of Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism supported his claim, made during a 1934 lecture, that the movement had “spread like wildfire, on pursuing its course, not only in art but in life”.

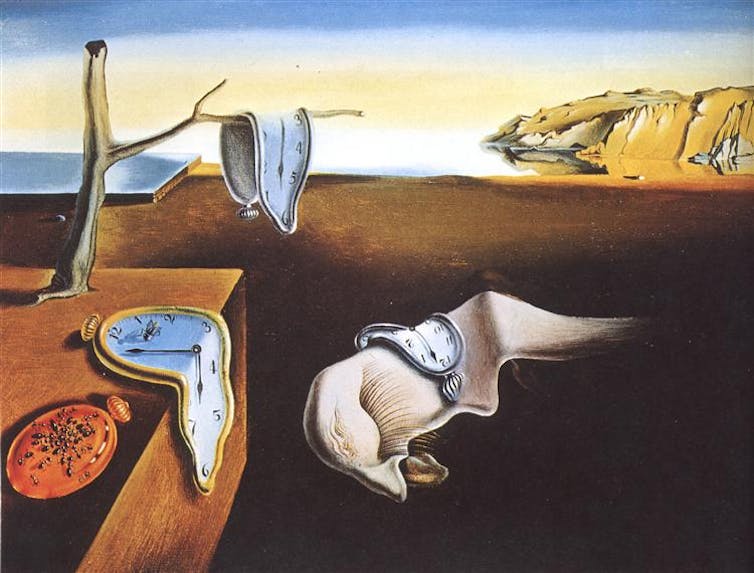

Surrealism’s public profile expanded internationally, along with its adherents. Luis Buñuel, Frida Kahlo, Aimé Césaire, Lee Miller, Salvador Dalí and Leonor Fini are just some of the important figures who embraced the movement.

Salvador Dali

And as the raft of high-profile exhibitions currently taking place confirms, the surrealist spirit lives on, decades after the movement wound down. Unabated, the search for the marvellous continues.