The popularity and durability of David Hockney’s art, through all his shape-shifts and restlessly inventive experiments, are really no mystery. His work is admired — loved is not too strong a word — by the millions who, worldwide, flock to see it because it presupposes an expectation of pleasure. No prior immersion in learned literature is required for admission to Hockney’s many gardens of visual delight, much less the opaque theorising that can tyrannise writing about contemporary art.

In March 1979, he wrote a piece for the Observer newspaper protesting against the Tate Gallery’s bias for abstraction, insisting that although “we know, in fact, that art can be full of joy”, the institution’s partiality for “joyless and soulless and theoretical art” embodied condescending arrogance towards public taste. For anyone wanting to narrow the distance between the “art world” and the public, Hockney’s unapologetic striving for the rejoicing of the eye must be a cause for celebration, not least because modernism and postmodernism have long had mixed feelings about the value of pleasure.

The demotion of sensory happiness to a species of mindless distraction began early, with Thomas Carlyle berating Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism, which sought the maximisation of happiness and pleasure for the many, as no better than “pig philosophy”: the grunt of animal satisfaction. Sigmund Freud’s essay “Beyond the Pleasure Principle”, published in 1920 in the bleak aftermath of the first world war, argued that the gratification of happiness operated as a sedative against agitation, a repression of the grim reaper lurking in the undergrowth of our subconscious. Modernists took note. The literary critic Lionel Trilling’s powerful 1963 essay “The Fate of Pleasure”, commenting on Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground, went so far as to describe modernism defining itself as the adversary of vain pleasure.

Art, in that view, ought never to be confused with the production of entertainment, the trivial bounce of the senses. The satisfaction of animal instinct, especially of cheerfulness, was the business of business: a conspiracy of enchantment designed to distract us from the otherwise intolerable inevitability of our mortality and the multitude of social and personal ills plaguing us en route to the door marked exit.

In the high-modernist canon, then, astringency is seriousness; the denial of joy, the condition of revealed truth. Strindberg and Schoenberg, Eliot, Sartre, and Huxley all recoiled at the vulgar satisfactions of mass culture in favour of what they held to be the deeper revelations offered by difficulty. Accordingly, much modern visual art organised itself around the repudiation of optical pleasure.

Some of the rejection of figuration was social and moral. The equation of pleasure-picturing with elite corruption has a long pedigree. Jean-Antoine Watteau’s “The Embarkation for Cythera” (1717) is said to have been the target of bread pellets hurled at it by Jacques-Louis David’s republican students during the French Revolution. The fact that the rescue operation of rococo ornamentalism by the Goncourt brothers took place at the height of the Belle Époque Second Empire, with all its associations of sybaritic despotism, only confirmed to moralising modernists that the delivery of voluptas was a drowsy vanity, a scrim veiling the brutal realities of modern life.

The culprit in this matter of art’s delusions, so its arch-modernist foes came to believe, was subject matter: the trap of depiction. (It is no accident that Hockney has said he much prefers “depiction” or “representation” to “art” as a description of his work.) Henceforth, as decreed by the high priest of abstraction’s theory, Clement Greenberg, painting was to be nothing more than the materials and designs from which it was constituted: colour and line laid down on an adamantly flat surface.

This theology of abstraction was in vogue when Hockney arrived at the Royal College of Art in October 1959. During the previous decade, British abstraction of the cerebrally elegant kind produced by Victor Pasmore and Ben Nicholson had rightly won admirers. But at the end of the 1940s, in Hockney’s account, their exercises in philosophical equipoise had been muscled aside by the attack painting of American abstract expressionism: Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Willem de Kooning.

For a brief spell, Hockney had a go at abstract expressionism himself, but recoiled from what he later called its barrenness. Subject-free painting was never going to be his way. The 1960s were at hand. Life in London was jumping and, as a lovely moment in Ken Russell’s 1962 BBC documentary Pop Goes the Easel reveals, so was David Hockney. Party-goers — among them Peter Blake and Pauline Boty, for whom subject-less painting was gratuitous visual dieting — are twisting the night away. But Hockney, crop-bleached hair, white jacket and those glasses, is merrily bouncing up and down like a prairie dog on speed. The pop-party people were making an art that, far from standing aside from mass culture, would become an integral part of imagining afresh the inexhaustible richness of the human comedy.

Including sex. While still at the RCA, Hockney had been making brilliantly scruffy, cartoonishly cottaging confections, queer stick figures in happy embrace, almost scratched into the picture surface like fingernails raking down a naked back. It was arte povera, with Kenneth Anger rather than Antonio Gramsci as its overlord. To my mind, “Doll Boy” (1960-61) and “We Two Boys Together Clinging” (1961) are some of the most original (and still wonderful) images that Hockney has ever produced.

Hockney rejected any kind of zero-sum game between cultural tradition and modernism. The bottomless reservoir of the canon — literary and musical as well as visual — could be fished for all kinds of performative experiments. Traditional subject matter — portraiture, landscape, still life, and genre painting — was not only perfectly compatible with figurative modernism, but could act as a tonic for rejuvenation. In New York in the summer of 1961, elated by the city’s playground of sexual freedom, Hockney began to revisit William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress for a series of etchings that he was to complete two years later. But Hogarth’s fateful morality tale ending in destitution, madness and disease is less evident in Hockney’s retelling than the joys of hedonism. “The Start of the Spending Spree and the Door Opening for a Blonde” features a profile of Hockney himself as the blonde in question, while a hot sun blazes behind that door, beckoning him towards a world of radiant sunlight and raunchy bliss.

Three years later, Hockney landed in California. “I instinctively knew I was going to like it,” he recalled, “and as I flew over San Bernardino and saw the swimming pools and the houses and everything and the sun I was more thrilled than I have ever been in arriving in any city.” A new visual vocabulary came to him to register the elements to which he most wanted to give form: light, space, water and, most famously, the places where they played together: swimming pools.

Water, especially, challenged him as a formal problem because, as he said, “it could be anything”, and, whether he knew it or not (and I suspect he did), some of the earliest, 17th-century drawing and painting manuals ask artists to accomplish seemingly contradictory tasks: the representation both of continuous surface and transparency. In the radical simplifications of California signage, Hockney intuited a way to fix elements that were, by their nature, elusively ephemeral: glancing diagonals for slanting light reflected off the curtain-glass wall of a modernist mansion, snaking patterns that became a visual shorthand for the lit ripples on the surface of a pool.

Freedom is a word Hockney often uses when he wants to describe his creative drive: the freedom from captivity to fixed-point perspective that enabled his glorious “Mulholland Drive” (1980), inviting the beholder’s eye along for the ride; but also freedom from whatever the current art-world dogma anoints as cutting-edge cool. I know of no other artist who has taken classical Chinese landscape scrolls, with their demand for a horizontally travelling eye, the country left behind rolled up as the next vista opens, as an analogous prompt for motoring vision.

But then, past, present and future are all indivisibly joined in the scroll of Hockney’s reinventions. His receptiveness to whatever the world has to offer by way of depiction has allowed him to embrace technologies — Polaroid photography, iPhones and iPads — in ways unimaginable to anyone for whom they represent mechanical or electronic banality. The work that often results is the opposite of a short-cut; rather, it is a revelation of eye-opening wonder, almost akin to the creation of medieval stained glass in a Gothic cathedral. Just as there was no division in that sacred work between makers and worshippers, Hockney’s pursuit of visual joy, I think, has always presupposed his unaffected inseparability from those who are going to consume it. In the bravest sense imaginable, his enthusiastic co-option of mechanical and digital devices is an act of faith: in the power of art to prevail over the shallowness of vision and disposable impermanence of Snapchat and Instagram.

Companionship, not invariably a characteristic of great artists, has always been at the heart of Hockney’s work; his portraiture is most expressively rendered when his subjects are friends or family, the attentive capture of a look the result of sympathetic affinity. Lucian Freud’s position vis-à-vis his subjects was that of the sovereign captor-creator, holding them hostage until the work was completed. When the two artists agreed to make portraits of each other, Hockney sat for 120 hours (by his own count), while Freud granted him three.

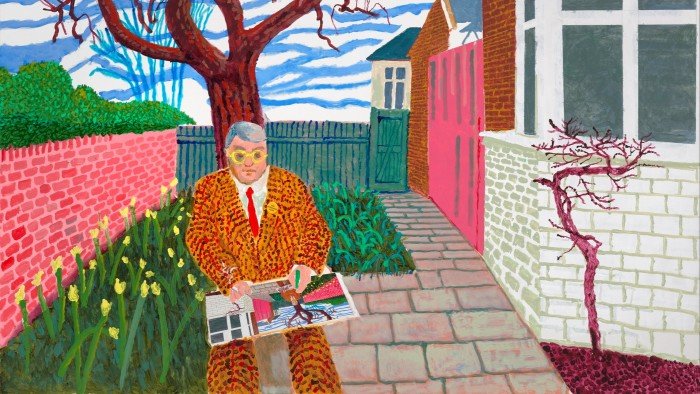

Hockney, on the other hand, is nearly always tenderly generous, never in a spirit of flattery but rather one of humane revelation. Not least of himself. Self-knowledge matters to David Hockney, with the result that his drawn self-portraits can be unsparing, amused or reflective, just (as he would say) the way he sees it. Most recently, and most movingly, he has depicted himself seated in a setting guaranteed to generate happiness: a back garden, the suburban version of a monastic hortus conclusus, though the artist, agelessly rendered, from the happy splendour of his tweed suiting and everything we know and everything he has done, is no cloistered monk.

The scene and the artist at its centre, his eyes cast down as he makes the paradise garden we are looking at, are situated both in the here and now and in memories of then; a happy scramble of the senses. It is a struggle, of course, not to see the picture as valedictory, summoning up as it does, especially for an artist so steeped in the history of his craft, other quizzically arresting late-life greetings to companion beholders: Pieter Bruegel’s drawing of himself at his easel trying to ignore the “connoisseur” buyer; Vermeer’s enigmatic “The Art of Painting”, with the artist seen from the back; Rembrandt’s self-portrait as St Paul holding a Bible in a bemused expression halted somewhere between mortal surprise and sacred resignation.

But we must resist seeing this lovely picture as an envoi. There is work to do. Some techno-gizmo lies waiting in the wings for Hockney to transform into a tool of redeeming art, lightening the load of our burdened world. So perish the thought, not the man. As for the work, it is already imperishable.

This is an extract from ‘David Hockney’, edited by Norman Rosenthal, published by Thames & Hudson to accompany the exhibition ‘David Hockney 25’ at Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, to August 31

David Hockney hand-picks his greatest hits at Paris’s Fondation Vuitton

Read Jackie Wüllschlager’s review of a “riotously enjoyable” show that is the largest ever retrospective of David Hockney’s work

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning